NZ Financial Resets: Part 3: 1920 - Who Stole The Silver?

Legal tender silver coins debased, silver content reduced from 92.5% to 50% silver; the Britain/India/U.S. triptych.

…the Prince…is not the lord or owner of the money…It is therefore the property of those who possess such wealth…unless he were a slave ― Nicholas Oresme, Treatise on Money (c1358)

Next: Part 4a: Central Bank Conspiracies

Previous: Gold Confiscation

Home: New Zealand’s Financial Resets

[NOTE: Much of the detail for this essay is taken from newspaper reports of the day. While the links to the archived reports are given, the more important and detailed ones are reproduced in full here.]

New Zealand’s Financial Resets

PART 3: 1920 - Who Stole The Silver?

Part two of this series revealed how the New Zealand Government covertly confiscated citizens’ legal tender gold coin in 1914, using lies, war, and time to hide the theft. Children are not taught this at school. Nor have we been taught that the second precious metal coin, the silver, was debased to zero silver in two steps. Here in part three I discuss the first step; the 1920 Government facilitated theft of nearly half the silver from the coin. The given rationale for this was a red herring, and the real reason is revealed.

Summary

In 1920 New Zealand’s legal tender currency, the British sterling silver coin, was debased when the silver content was reduced from 92.5% to 50%. The official explanation was the high price of silver, which had doubled in the three years to January 1918, destroying Britain’s coinage seignorage. In truth this was at best a proximate cause, maybe true for only a few months when the silver price was high. The real motive for the removal in my opinion lies in deeper geo-political machinations and the economics of the 1914-1918 war.

A core aim of British power-brokers and planners in the late- to post-war period was to prolong their control of India, and silver was at the beating heart of this control. The basis of the currency, the rupee coin, was 91.7% silver. Silver backed India’s Government debt, and the ‘councils’ sold in London and used as a UK-India trading currency were payable in India on demand with rupees (i.e. silver). Silver also had an important role in the social and religious life of the 300 million population.

The outcome of the war was far from certain in January 1918 and it could still have gone either way.1 As the war became critical, Britain’s hold on India was looking shaky. There must have been heavy concern among the British ruling class at both situations, which were inexorably linked; India was a crucial supplier to Britain and the allied war machine. Instances of open revolt against British rule were growing, and there was a significant and strengthening independence movement. The printed rupee note supply, expanded over the war, was left with only 6% rupees in reserve, despite the minting of 200 million during the war.

Globally silver was scarce, expensive and couldn’t be shipped even if it was obtainable. So the rupee currency was on the verge of collapse. Were this to happen the result would probably have been open revolution and the possible rapid loss of India. This would have been catastrophic for Britain, which had expended its treasure and accrued a war debt of £7 billion, while much of Britain’s industrial business model added value to India’s labour intensive but cheap raw materials.2

My guess is British powerbrokers saw the writing on the wall and were desperately trying to prolong their presence in India as long as possible, to extract every last drop of wealth from the country possible while retooling their domestic industrial capacity.

In an urgent and secret move the British approached the United States and negotiated a deal to buy 200 million ounces of melted down silver dollars at $1 per ounce. An Act of Congress was required, and the Pittman Act (1918) was passed secretly in record time. The silver, which was supposed to be part of the backing for U.S. debt issued during the war, was shipped and soon minted into rupees. India was saved for the moment, but Britain certainly paid.

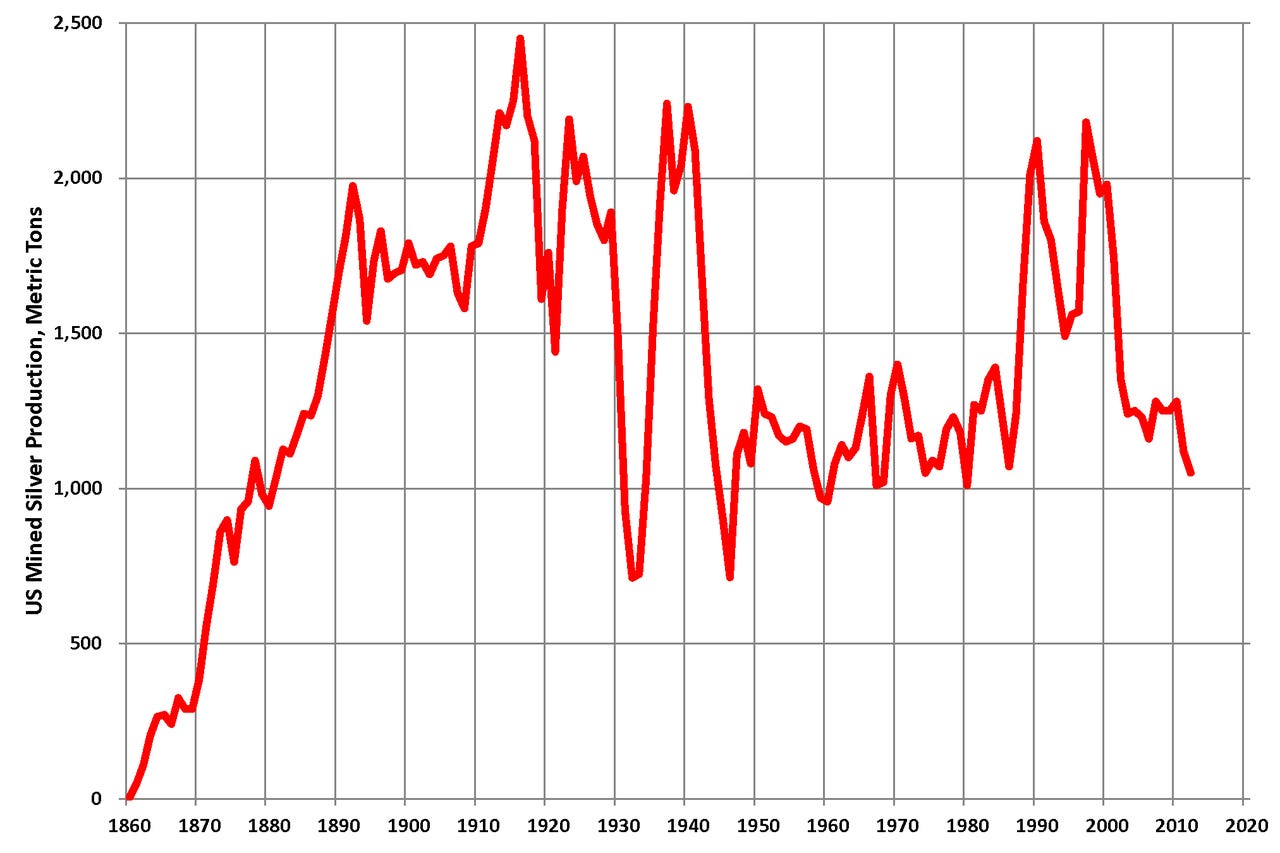

The deal worked out (or was made to work out) very well for the United States. They replaced their sold silver dollars by purchasing silver from U.S. domestic mines, which was a boon for that industry in more ways than one. A few months after the U.S. Government started buying the replacement silver in mid-1920, the market price collapsed,3 precipitously, so for nearly all of the thirteen years the U.S. Government was buying domestically for one dollar, the silver market-price was 40-50% lower. The U.S. was buying, the U.S. mining industry was getting what amounted to a heavy subsidy, but Britain was paying. And of course the price collapse removed the rationale for the debasement of British coin.

The silver price collapse suited the United States because their mining industry, selling large amounts domestically for $1 per ounce, thrived while the rest of the world’s mining sector struggled on the much lower global market price. The price collapse suited Britain because it helped strengthen their very profitable hold on a fractious India, albeit temporarily, and freed up silver for other purposes.

The price collapse probably also suited the other war belligerents as most were using silver in their coins or to help back their notes, and my guess is their metal reserve ratios had also suffered badly during the 1914-1918 period. There is a good argument to be had, with strong circumstantial evidence, that U.S. actors were responsible for the price suppression, with Britain’s moral support. No other nation had the financial or metal resources in 1920 to undertake such a massive price manipulation.

Britain needed silver for India, and lots of it

Britain needed to sell everything possible to repay their enormous war debt, including the $200 million plus borrowed to purchase the silver in the secret Pittman deal

Britain had expended its treasure and needed to rebuild it’s own gold and silver reserves

Britain had good reasons, from the perspective of its ruling class, to remove the silver of the coin and debase their currency. The short term price spike, useful and used as the justification, was not the real cause.

My conclusion is ultimately the British (hence New Zealand) coinage was debased and sacrificed in 1920 to save India for the British and as a part of British strategy to repay their massive war debt. And the United States Government, who profited immensely from the war, also did well from the ‘little’ side deal on silver; especially U.S. miners who had over a decade of significant advantage.

The only people who lost in the deal were the British and New Zealand public, who lost half the intrinsic value of their coin. In the case of New Zealand, we took the second step towards a pure debt based fiat currency.

Read the full story below…

Who Stole The Silver?

1830s New Zealand saw seamen of many nations meet to replenish supplies. Most transactions were in cash and in consequence silver and gold coins from around the world with varied weights, sizes, and precious metal content, were in circulation. It wasn’t until 1845 that a sufficient supply of British specie coin arrived in the country that other coin started to disappear from circulation. In 1858 British sterling coin became the only legal tender coin in New Zealand.4

Before 1920 British coin denominated three penny and higher was minted from 92.5% silver, known as ‘sterling silver’. In September that year, when the populace were still recovering from the 1914-1918 war, the British Government reduced the silver content of the coinage to 50%. There was symbolism aplenty; as the sun was setting on the British Empire, the King’s shilling was being debased.5

Despite being one of the most significant events in New Zealand’s financial history to that date, our Government was essentially silent about this obvious debasement of the currency and theft of the value of the coin. There was some coverage in the press, and the debate in the UK was reported in the “cables” in New Zealand. Legal necessities to adopt the debased coinage were satisfied a few days later via a Proclamation in the New Zealand Gazette.6

There were alternatives available if the Government had wanted to protect the value of legal tender coin and the interests of New Zealanders.

The British specie silver coin had originally been accepted for settlement of debt (i.e. its value) because of its high silver content and guaranteed characteristics (weight, size, metal content). Its legal tender status was secondary. When recognised a British shilling was accepted around the world where it wasn’t legal tender because the silver gave it intrinsic value.7

The argument given publicly for this debasement was the high price of silver, which had doubled over the war years then reaching a high in 1919 before quickly declining about ten percent where it remained for most of 1920.8 At the high price it was claimed there was no profit (seigniorage) in minting the coin, which was true only for a short period longer, until the price collapsed in late-1920 early-1921.9

The Dominion published in mid-1921.

Silver was quoted by cablegram at the end of last week at 35.25d., so that British coinage is safer than ever. Apparently, however the Treasury intends to persevere in the policy of issuing the new coins.10

The size and speed of the silver price increase was not a reflection of significant military hardware use. In the absence of available gold, which was withdrawn by belligerent nations to support the expansion of debt, silver was in demand both to support gold in backing the debt, and as a medium of exchange. There was growing demand, especially among belligerents, simultaneous with global production decline.11

The Silver Market: 1914 - 1921 and Beyond

Silver, as mentioned above, had undergone a rapid price rise during the 1914-1918 war, more than doubling over that period, before declining in January 1920.12 Prices on a per troy ounce basis.

December 1915 USD ~0.5 (GBP ~27d)

December 1916 USD ~ 0.6 (GBP ~32d)

December 1918 USD ~1.1 (GBP ~80d)

December 1919 - January 1920 USD ~1.1 > ~1.0 (GBP ~80d > ~72d)

December 1920 USD ~1.0 (GBP trading range 50d to 60d)

The silver price had given every indication of stabilizing; it had reached a high and pulled back 10%. The war was over and global demand was still strong, especially in Asia. India secured the equivalent of three years total global production in 1919 alone. Despite the British decrease in silver demand for coinage due its coin debasement a few months earlier, the extent of what happened next must have given those that were not insiders a shock. The price collapsed about 40%. Silver was not going to see the same price for forty years.13

December 1920 > January 1921 USD ~1.0 > ~0.6

May 1921 GBP 35.25d14

There was certainly vested interest in reducing the silver price [emphasis added]

…It is believed that except by concerted Governmental action to check the rise in the price of silver, the silver coin of the world will go into the melting pot. If…prices go higher the Governments will be coining silver at a loss—hitherto there has been considerable profit to the State, known as seignorage...POVERTY BAY HERALD, 7 MARCH 1918, PAGE 2

Was there “concerted Government action” to drive the price down? Given the ‘fishing line’ nature of the price collapse it looks like it. A major force which drove the price of silver up over the war years which became the rationale for the debasement of British coin, were events in India, discussed below.15

What caused the silver price collapse in 1921-1934?

We can only speculate at this distance in time as to how the price collapse was achieved. My guess is that commercial and banking interests associated with Britain, India and U.S. mining are responsible, with the support of the other war belligerents. All their currencies, notes and/or debt were associated with silver in some way. A lower price suited them all.

Only the United States had the financial resources in 1920 required to drive the price down 40% in such a short time, and being the world’s largest producer they had the metal resources to sell to the U.S. Government at the high price of one dollar, and on the open market at the much lower price to keep the world’s market price suppressed. Though this is speculation there is a bounty of circumstantial evidence.16

India’s currency and silver situation

India was considered the ‘jewel’ in the British crown, and an extremely lucrative jewel it was too. By 1914 the country had been a major source of goods to British consumers and robust profits to British manufacturers and investors for over two centuries. But there were storm clouds on the horizon. A growing independence movement was agitating to remove the British from India, and the British administration was very focused on maintaining control and pacifying the country. A strong currency, the silver rupee, was crucial to achieving these aims.17

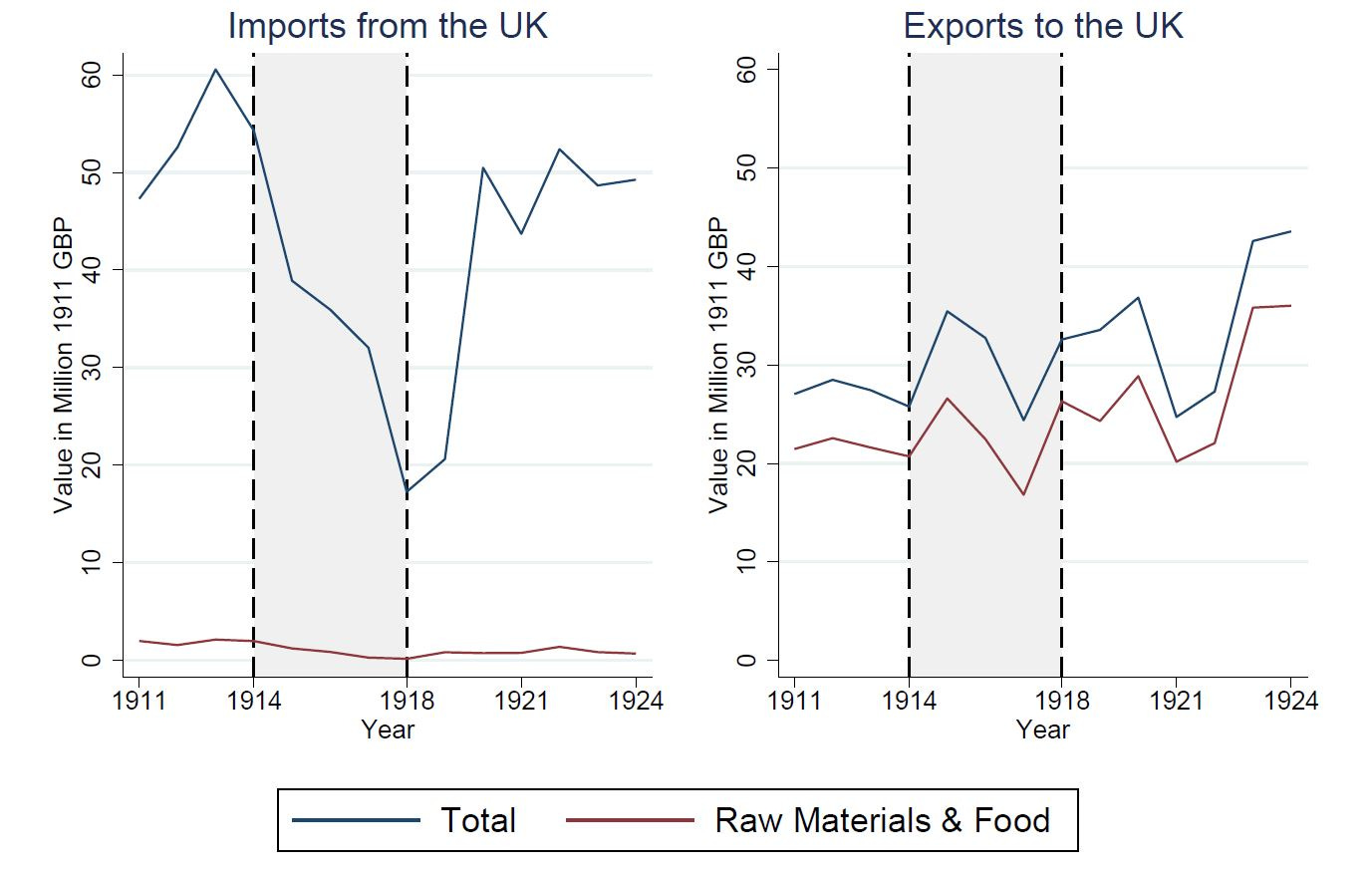

The British supply chain was heavily dependent on India during the war. Two thirds of India’s population lived in the countryside with few banking facilities, so the ‘ryot’ hoarded surplus rupees. The ryot also demanded payment in metal. They wouldn’t accept the paper rupees then in circulation so by the end of 1917, after a good crop, India was drawing three quarters of all silver produced in the world. During the war, imports into India from Britain declined by two thirds and, of the goods that could be imported, inflation had doubled prices.18

The consequence of this unavailability and unaffordability was increased rupee hoarding and the velocity of its circulation plummeted. Rupees were also being melted down in large quantities. Silver was replacing gold in the social and religious life of the population of 300 million as gold shipments had stopped and the only source of silver for most people was the coin.

The situation was made worse for India by two further facts; the silver rupee was widely accepted across Asia, adding to domestic-supply pressure, and India’s Government debt was backed by precious metals. The solution to overcome this problem was to buy silver on a larger scale than ever and mint rupees. Unfortunately global production of silver fell during the war, while in addition to India other countries became strong buyers.19

The silver price finally reached the point where it became profitable to melt rupees down. To eliminate this potential arbitrage, in August 1917 the Indian Government revalued the rupee against the pound sterling. But silver continued to rise and as gold and silver no longer flowed to India due to war restrictions “the financing of trade was entirely thrown on the…Government…[there was] no other way of settling the differences between exports and imports”. So India’s position worsened.20

At the beginning of 1914 India’s paper note currency was backed by 79% metal (gold and silver). By the end of 1917 India was drawing three-fourths of all the silver produced in the world, but despite coining 200 million ounces of silver in the three years to March 31 1918 silver reserves sunk to about 6% of note issue. The Government’s position grew desperate and it seemed inevitable that they would have to announce the inconvertibility of notes, which had reached a discount of 19% in the Indian bazaars.21

The whole structure of India’s currency was in peril. That meant the jewel in Victoria’s crown was threatened. Silver had to be supplied to India to avert a financial panic and full-blown revolution.

The U.S.A. to the rescue

By early 1918 Britain was in no position to come to India’s assistance. Aside from expending vast amounts of its treasure of gold and silver, its national debt was approaching an astronomical £7 billion. India (i.e. Britain) turned to the U.S.A. which had “vast stores” of silver dollars. Rapid legislation, the Pittman Act, was passed through Congress in April 1918 making 200 million ounces of silver available for India at $1 an ounce. This was shipped as rapidly as possible, and at the same time another 120 million ounces were bought on the open market ”though at tremendous prices”.22

That the U.S.A. helped India over one of the most serious financial crises in the history of the British Empire was confirmed by Sir James Meston of the Viceroy's Council who emphasized how vital to India's war contribution the Pittman Act was, which released the silver for use in alleviating the currency situation there. He said India and the British Empire and the Allies owe a debt of gratitude to the United States, which “is hard to over-estimate”.23

The Bombay Mint was kept working night and day, the position was saved and India's credit maintained. Confidence gradually returned, and in 1919 the highest discount reported on the note was 3%. India’s silver reserve increased 10X in 1919 to give a metallic reserve of £83,000,000 and anxieties of Government maintaining convertibility were eased.

In early 1921 the U.S. Treasury announced that Great Britain had paid $25 million on account of her silver debt. That same year the new Viceroy of India, The Earl of Reading, shed some light on the circumstances in which Great Britain came to need and to receive a large supply of silver from the United States.

“There was a moment at which we were very hard-pressed to find the metallic reserve, particularly the silver which was necessary in India, it being incumbent that the paper note issue should be convertible immediately into the silver rupee. Our difficulty was to find the silver. There was no means but one; that seemed impossible. In the vaults of the American Treasury there were vast stores of silver, preserved there as the financial backing against the notes which were issued—silver which could not be disturbed, no matter how much it was wanted. It could not be taken out of the vaults of the United States save by Act of Congress.”24

Lord Reading related how the U.S. Administration, and the members of Congress, of both parties, solved the difficulty by passing an Act of Congress without discussion “because discussion would have been serious.” The measure was enacted in almost record time, and became law within a few days. The millions of ounces of silver from the vaults were released and were shipped to India.

So,

200 million ounces of U.S. silver, an enormous amount of treasure, was secretly sold to Britain,25

for export to India in order to support its paper rupee notes which were collapsing because they were backed by only about 6% of physical silver.

The secrecy of the deal may have had something to do with the fact this silver was security for some of the United States’ note issues.26

Given the already precarious nature of the British foothold in India and the growing independence movement, failure of the rupee could have resulted in open revolution, and quickly. This silver purchase was part of a desperate attempt by the British to retain control over India, if only for the time being.

This was a good, if not fantastic, deal for the United States. They had sold Britain an enormous amount of silver for the near record high price of $1 per ounce, plus mint charges. Silver that was supposed to be backing some of their note issue, hence the secrecy. And Britain paid with debt, debt which must have had interest attached.

Fast forward two years to 1920, and the United States started a 13 year buying and re-minting regime, buying only from U.S. mines, and paying the mines $1 per ounce. For nearly all those 13 years the market silver price ranged from $0.6 to $0.3, so the U.S. mining sector was in effect getting a large subsidy. Only it was Britain actually paying.

The cost of war and empire.

Towards the end of 1921 the New Zealand Herald reported27

Coinage of silver dollars has been resumed by the United States mint after a lapse of seven years, and the work of replacing 279,000,000 standard silver dollars taken from the Treasury during the war to sell to Great Britain has begun.

The U.S. mining sector thrived over these years. Silver is normally a secondary product from the mining of other metals such as copper, lead, gold, and zinc. In May 1921 the Evening Star reported

With the price of silver fixed at a dollar an ounce, under the Pittman Act, the silver producer in the United States is favored compared with the…outside competitor, who has to accept current market prices…the Pittman Act permitted the…exporting of…207,000,000oz…This…was to be replaced by purchases of silver produced in the United States at a dollar an ounce. Such purchasing began in May…The silver produced in the United States…is mostly by-product, and the fixed price of the silver has been of great importance in aiding the lead and copper producers to make “both ends meet.’’ The lead ores of the Rocky Mountain district are rich in silver content, and in taking advantage of the price of silver under the Pittman Act, which is practically double that ruling in the foreign market, lead is bring produced largely as a by-product of silver, instead of silver a by-product of lead, as in ordinary times. This explains to a large degree why domestic lead can be sold at present low prices by many producers in America, while other mines cannot afford to produce the metal. …EVENING STAR, 24 MAY 1921, PAGE 10

The last point was poignant for Waihi gold and silver mines’ employees and owners. In April 1921 the Waihi Daily Telegraph reported on union demands for a cost of living wage increase. [ ] added.

Mr Rhodes [owners representative for Waihi G.M. Company mine] pointed out that the cost of operating the Waihi G. M. Company's mine had risen…during the past four years, with the result that the average value of the ore…if based on the normal price of gold and silver, would leave the owners without profit. The only thing…for…profit shown was the inflated prices of the metals…Since the last agreement the price of silver had dropped, from 6s per ounce to well under 3s, and gold had receded…by 12s per ounce. These reductions…coupled with high production costs, had made it necessary for the directors to reduce dividends…by half. In order that the men might be satisfied that the position was as he had stated he was to admit of the examination by an accredited accountant, to be appointed by the union, of the company's costs sheets. It was impossible in the circumstances for the mine owners to grant any increases. …WAIHI DAILY TELEGRAPH, 20 APRIL 1921, PAGE 2

The Pittman Act’s sponsor, Senator Key Pittman from Nevada, had strong connections to the mining industry, especially silver mining. Nevada is still called the ‘Silver State’ for a reason, and mining was, and is, very important to the state. So the Act that bears his name served his state well.

Britain’s other India problem

Britain’s issues with India were also domestic. The trade balance, plus costs incurred over the war years, left Britain owing over £400 million to India by war’s end. But there was a big problem…payment. Only a fraction of the gold and silver available before the war could be obtained, and because silver to mint rupees was scarce in India the ‘councils’, redeemable in rupees, could not be sold in desired amounts. Britain could only raise £136 million, not nearly enough to pay the trade balance owed, let along the costs.28

Britain’s other United States problem

Britain had borrowed $4 billion from the U.S. Treasury in 1917–18.29

Meanwhile, back in New Zealand

The impression to be gained from newspapers of the day is that the population’s understanding of, and interest in, issues of money, currency, silver and gold was high before and after the war. Stories were many, detailed, nuanced and often appeared in even the smallest newspapers, so most reading people were at least exposed to different schools of thought. Which makes the visible public response to what happened when New Zealand’s coin was debased surprising.30

Essentially there was silence. Or maybe the press just didn’t report what must have been very controversial.

Either-way, the population must have still been shell-shocked from the war, nine thousand deaths from the (supposed) Spanish flu, and the deteriorating economic conditions leading up to the depression, so there was plenty to distract.31

The Imperial Coinage Act 1920 proclamation was gazetted in New Zealand in mid-September that year and the debased British coin became legal tender. Meanwhile silver coin was disappearing from circulation and by October it was being reported that the the country was experiencing a shortage.32

The population was being told the debasement was because the public had “been receiving more than a shilling's worth of silver in a shilling”, at the very same time the silver price collapsed. Though the price didn’t return to pre-war levels, there was still plenty of seignorage profit for sterling silver coins at the new price. If the Government that wanted to retain the value of the nation’s coin.33

The reason given was no longer valid by the time the first debased coins arrived in New Zealand.

Alternatives for New Zealand

The New Zealand Government had options if they had wanted to exercise some independence from Britain and retain the 92.5% silver content, hence the value, of the coinage. Rather than ratify the Imperial Coinage Act there were three alternatives available to the New Zealand Government immediately, though each had different implementation timeframes:

use Australian coins, as legal tender currency.

mint New Zealand coins at an Australian or other mint.

mint New Zealand coins at a New Zealand mint.

Option 1: Australian coinage was already widely used in New Zealand. This option would have retained the intrinsic value of the coinage; it was 92.5% silver until they finally debased to 50% silver in 1946. This theoretically could have been implemented immediately with a gazetted Proclamation to make it legal tender, as was done in 1897 to apply the British Coinage Act 1870 (amended 1891) in New Zealand. Ultimately the country would have been dependent on the ability of the Australian mints to produce and supply sufficient quantities of coin.34

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) claims about 40% of coins in circulation by 1931 were Australian legal tender coins. Though the RBNZ doesn’t identify proportions of silver and copper, it is safe to assume at least some were silver, all 92.5%.35

Option 2: This would have required a coin design and capacity at one of the global mints. The Government would have profited from the seignorage but incurred minting costs on top of shipping. The amount of seignorage would have become a political matter; a positive or negative depending on your perspective.

Option 3: The most expensive and complex alternative in the short run, ultimately the rational for creating a state mint would be domestic retention of seigniorage profit and the control of supply. A decade after the debasement, in 1931, the issue of minting New Zealand coins in New Zealand came up as a Bill in Parliament.36

The above is a caricature of what would actually be required to implement a new coinage regime in the reasonably sophisticated society that New Zealand was in 1920, but it doesn’t matter. The discussion was never held. New Zealanders were presented fait accompli with the debased British coinage. Maybe this was just the easiest way forward for the Government.

And what did the British Government do with the silver they had removed from the coinage? That I don’t know. It could have gone to India. It could have been sold on the open market. It could have been minted into 50% coinage. My guess is probably a bit of each. The British had so much debt after the war they were selling anything that moved, and if it didn’t move they kicked it first, then sold it.

Meanwhile, New Zealand had taken a second step, moving a little closer towards a pure debt based fiat currency, when half the silver was removed from our coin.

Next: Part 4a: Central Bank Conspiracies

Previous: Gold Confiscation

Home: New Zealand’s Financial Resets

It nearly did. See German spring offensive.

This is one aspect of mercantilism.

The silver price was not going to reach the same level again for forty years.

“were in circulation“ - For example gold mohurs and silver rupees from the East India Company, Spanish-American doubloons, U.S. dollars, Dutch ducats and guilders, French francs and British silver and gold coins.

Hargraves, R.P., “From Beads to Banknotes”, John McIndoe Limited, Dunedin (1972), p26.

“started to disappear from circulation“ - Hargraves (1972) p 53.

“the only legal tender“ - silver coin was legal tender for transactions up to two pounds.

“The coinage situation was clarified by the English Laws Act 1858 that extended the laws of England, including the Coinage Act 1816 (UK), to New Zealand, thus retrospectively giving undoubted legality to the use of British coins in New Zealand” Matthews, K., “The legal history of money in New Zealand”, Reserve Bank of New Zealand: Bulletin Vol. 66 No. 1

“sterling silver” - 92.5% silver in any context (e.g. coin, jewelry, cutlery, plate) is known as ‘sterling silver’ to this day because it was the silver content in the British ‘pound sterling’ currency’s coin. Before 1920 the coins of the sterling currency in circulation composed of sterling silver were: 3p, 6p, shilling (= 12p), florin (= 24p), half-crown ( = 30p), and the less common crown ( = 5 shilling = 60p) [p = penny]. Maundy money, non-circulating coin, was the exception. A gold sovereign worth £1, containing 0.2354 troy oz of pure gold was worth 20 shillings. The 1914 shilling weighed 5.66 grams, or 0.168 troy oz of silver. So the sterling currency was based on a gold/silver ratio of 20*0.168/0.2354~14:1.

**********************************

See DOMINION, 31 MARCH 1920, PAGE 7 for some history of the pound sterling currency.

**********************************

“British Government reduced the silver content“ - Imperial Coinage Act 1920.

“Took the King’s shilling” - refers to the past practice of the British Armed Forces paying a one shilling enlistment bonus. Though the practice had been officially abandoned, the expression "take the king’s shilling” was widely used in the British media and popular culture in 1914 when young men were enlisting for the war. It was reported on by New Zealand media so it can be assumed it was in common usage here too.

Examples of “king’s shilling” used in media and popular culture in 1914 New Zealand:

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers?end_date=31-12-1914&items_per_page=10&page=2&phrase=2&query=king%27s+shilling&snippet=true&start_date=01-01-1914

“Government was essentially silent“

I couldn’t find any criticism of the debasement in the parliamentary record (Hansard) or in the press of the day. Hargreaves agrees.

In New Zealand the debased coins appear to have been accepted without any discussion.

Hargraves, R.P., “From Beads to Banknotes”, John McIndoe Limited, Dunedin (1972), p137.

“some coverage in the press“ - for example

DOMINION, 17 SEPTEMBER 1920, PAGE 10

NEW ZEALAND HERALD, 20 SEPTEMBER 1920, PAGE 4 - BRITISH COINAGE ACT.

[Note: “275” in this article is incorrect. It should be 075.]

TARANAKI HERALD, 16 DECEMBER 1920, PAGE 3 - NEW SILVER COINS TO CONTAIN LESS SILVER IN CIRCULATION IN BRITAIN.

“reported in the cables“

EVENING POST, 15 DECEMBER 1920, PAGE 9

The matter was debated at some length, as readers of the cables will recollect, but the measure was passed.

“Proclamation in the New Zealand Gazette“ - New Zealand Gazette No. 80, 16 September 1920, pp2650-2651

Globally, specie silver coin of any nation was accepted at the silver value if the coinage hadn’t been debased. Non-legal tender silver specie coin likely wouldn’t have had the same purchasing power it had in its legal tender jurisdiction.

Silver price, 1915-1950 - Raw and Inflation Adjusted

a) Raw silver price

https://silverprice.org/

b) Inflation adjusted silver price, base January 2024

https://www.macrotrends.net/1470/historical-silver-prices-100-year-chart (note: the x-axis on this chart is adjustable).

DOMINION, 17 SEPTEMBER 1920, PAGE 10

STANDARD FINESS OF SILVER COINS

…silver is very much more costly now than it was before the war, and the actual value of the pure silver in a coin will probably be equal to the face value of the coin, that is to say, the silver in a half-crown would probably be worth very nearly 2s 6d. If the value of the silver is less than this, the mints will make a profit out of the silver coinage…

My heavily edited version of the Dominion article gives what was probably the crux of the official line on the silver coin debasement. Some facts. Some ideology. [ ] mine.

The change in the composition of British silver coins was prompted by the great increase in the price of silver during the war and post-war period. Immediately before the war…an ounce of silver sufficed for coins to the value of 5s 6d…the minting of silver coins was…highly profitable to the British Treasury. The margin was sufficient to cover a great increase in the price of silver, but on February 11 last year the price of the metal touched…89.5d., nearly four times the pre-war price…price was the highest since statistics have been systematically recorded…it became profitable…to melt down British silver coins and sell them…In February, 1920, the profit on this…was over 33 per cent., and the profit remained considerable even when the price of silver had fallen to some extent.

With matters in this state, the British Treasury announced that a Bill would be promoted to reduce the fineness of the silver in coins from .925 fine to .500 fine…Long before that time [the introduction of the coins] the price of silver had fallen far below the point at which the illegal melting down of silver coins was profitable. At the end of the year the price was about 40d. per ounce, at which figure the melting down of silver coin would involve a loss of about 40 per cent. To what extent British silver coins were melted down during the period of extremely high prices does not seem to have been stated with authority...Some complaints have been made that the reduction of the amount of silver in coins debases the coinage, but this is an erroneous view. British silver coins are "token money,” and are legal tender only to an amount of £2. Even before the war, they were worth intrinsically much less than their face value, and the present reduction carries no such consequences as would the reduction of the amount of gold in a sovereign. …DOMINION, 14 MAY 1921, PAGE 8

“military hardware use“ - Silver was used for medals, important for morale and propaganda, and in the coin used to pay soldiers, but not in armaments (unlike today).

“medium of exchange“ - POVERTY BAY HERALD, 7 MARCH 1918, PAGE 2

GOLD AND SILVER.

… the enormous increase in the indebtedness of the belligerent nations, reaching to something like twenty billon pounds. …"The demand for silver," says the Journal of Commerce, "is the largest experienced for years. The usual requirements of the Far Eastern countries, China and India, and in Mesopotamia and other Asiatic countries, have expanded with the increase in exports and in prices. But of more importance has been the growing demand for silver for coinage in European countries, notably England and France. In order to finance the war it has been necessary to withdraw all gold from circulation as far as possible to furnish the basis of credit expansion, and silver has come into use as a principal medium of exchange.

Most countries used a fractional reserve system and tried to back their currency creation with 40-45% by value gold and/or silver. During the war this ratio collapsed…getting as low as less than 10%. GOLD AND SILVER. POVERTY BAY HERALD, 7 MARCH 1918, PAGE 2

“global production decline“ - Press reports discussing global silver production and demand before, during and after the war [emphasis added].

Production

POVERTY BAY HERALD, 7 MARCH 1918, PAGE 2

GOLD AND SILVER.

…it is expected that 100 million ounces will be available in the current year.

OTAGO DAILY TIMES, 28 AUGUST 1920, PAGE 6

THE RISE IN SILVER AND THE INDIAN EXCHANGE.

…the world's production of silver fell from an average of 228 million ounces before the war to 178 million ounces during the war, while in addition to India other countries became strong buyers…

Demand

STAR (CHRISTCHURCH), 27 NOVEMBER 1918, PAGE 4

VALUE OF SILVER. BECOMING RARE AS GOLD. WHERE THE MONEY GOES.

…And though you can still obtain silver, the fact remains that in proportion to the demand…silver is becoming…rare as the rarest metal. Is the day coming when silver…will …disappear in the invisible "sink" that absorbs precious metals in times of war?…

FEILDING STAR, 5 NOVEMBER 1919, PAGE 2

THE SHORTAGE OF SILVER.

…there is…a shortage of silver…silver is soaring also…there is such a demand for silver…that people in the Home land are selling their family plate, for melting down, and the British Government has prohibited the melting down of silver coins. Silver by the ounce has not been so highly priced in England since 1807…It is said that the scarcity is not only due to the return in popularity of silver jewellery (and also to the making of millions of war medals and ornaments), but to the pecularity [sic] of the native people of India in hoarding silver. Since the war begun the natives of India…have absorbed £20,000,000 worth. What silver they do not convert into ornaments…[they] bury in the earth…The peasantry of hoarding habit. So that silver will still soar in price.

Price references:

VALUE OF SILVER. STAR (CHRISTCHURCH), 27 NOVEMBER 1918, PAGE 4 (16 days after armistice)

…the Treasury fixed the maximum price for silver at 1 dollar 01.5 cents…

THE SHORTAGE OF SILVER. FEILDING STAR, 5 NOVEMBER 1919, PAGE 2

…to-day—5s 1.25d oz

THE SILVER MARKET. GISBORNE TIMES, 20 JANUARY 1920, PAGE 5

Jan. 15. Silver slumped to 79d per standard ounce

Jan. 15. Silver is quoted at 77d per standard ounce

THE RISE IN SILVER AND THE INDIAN EXCHANGE, OTAGO DAILY TIMES, 28 AUGUST 1920, PAGE 6

1915 27d, 1916 36d, 1917 50d, 1919 78d

NEW SILVER COINS. TARANAKI HERALD, 16 DECEMBER 1920, PAGE 3

Ag < 30d/oz converted by mint into 5s 6d [=66d] worth of coins at the mint.

During war > 82d/oz.

“India secured the equivalent“

OTAGO DAILY TIMES, ISSUE 18026, 28 AUGUST 1920, PAGE 6

THE RISE IN SILVER AND THE INDIAN EXCHANGE

… India secured altogether 538 million ounces of silver, or the equivalent of three years of the world's production…

“British decrease in silver demand“

Their demand was still strong; the UK Government bought 1.7 million ounces in 1920.

AUCKLAND STAR, 1 JANUARY 1921, PAGE 5

COINS AND MEDALS. MINT BUYS SILVER. BIG GOVERNMENT BILL.

LONDON, December 20. In the House of Commons, Mr. Austen Chamberlain (Chancellor of the Exchequer), replying to Mr. J. G. Hancock (C.L.), stated that the Mint in 1920 bought 200,000 standard ounces of silver bullion for coinage and 1,500,000 ounces for medals, at an average price of 4/8 an ounce [= 56d].

“fishing line’ nature“

i.e. the price went straight down.

In 1920 the U.S. produced about 1500 tonnes of silver = 1500 (tonne) x 1000 (kg/tonne) x 32.15 troy oz/kg = 48.2 million ounces. The U.S. bought 39.2 million ounces over this period (EVENING STAR, 24 MAY 1921, PAGE 10) leaving 9 million ounces which, unless it was stockpiled, must have been sold on the open market. My guess is this excess was offered at lowering prices on the open market for the thirteen years the U.S. Government was purchasing at $1 per ounce. Though it represented only about 10-15% of global silver production this would easily have been enough to drive the price down 40% plus, which is what happened for the whole period (1920-1932). The silver price began reversing its thirteen year downward move at the end of 1932.

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silver_mining_in_the_United_States

“remove the British from India“

In 1919 the British had massacred many hundreds, possibly thousands, of peaceful protestors in the city of Amritsar and the country was aflame with protests, boycotts of British goods, non-cooperation and civil disobedience. In that same year the Indian Government passed the Government of India Act 1919 which gave limited participation to Indians in government.

Mahatma Gandhi had returned to India in 1915 and quickly became one of the leaders of the independence movement. Despite his support of the British during the 1914-1918 war, by 1920 Gandhi had developed a large following, and India was (emphasis mine)

seething with sedition and open rebellion; it is rich ground for seeds of Bolshevism and revolution, which are coming into that grand and glorious country from Russia and Germany, with ample gold behind it to make its influence the more deadly. TAIHAPE DAILY TIMES AND WAIMARINO ADVOCATE. WEDNESDAY, 7 APRIL 1920, PAGE 4

“the silver rupee“

91.7% silver content. For example 1/4 rupee, 1/2 rupee, 1 rupee.

“Ryot“

was a general economic term used throughout India for peasant cultivators and hired labour. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryot

“declined by two thirds“

Trade between India and the UK 1911–1924

https://www.e-ir.info/2020/08/10/trade-industrialisation-and-british-colonial-rule-in-india/

“widely accepted across Asia“

The rupee is accepted practically all over the East, because it is the only Eastern coin of silver using countries which has not undergone depreciation or debasement over a long series of years … KAWHIA SETTLER AND RAGLAN ADVERTISER, 2 JANUARY 1920, PAGE 4

“global production of silver fell“

From an average of c.225 million ounces before the war to c.175 million ounces.

“profitable to melt rupees down“

When the token value of the rupee (1s 4d) was equal to the silver content value.

“revalued the rupee”

From 1s 4d to 1s 5d on 28 August 1917. OTAGO DAILY TIMES, 28 AUGUST 1920, PAGE 6.

Revaluation continued for the next few years. By April 1920 the exchange rate was “about half-a-crown” (2s 6d). TAIHAPE DAILY TIMES AND WAIMARINO ADVOCATE. WEDNESDAY, 7 APRIL 1920, PAGE 4

“coining 200 million ounces of silver“

The Bombay mint had produced a record 307,707,326 rupees in the 1916-1917 year compared to 16,202,199 rupees the previous year.

DOMINION, 3 JANUARY 1918, PAGE 8

“astronomical £7 billion“

British debt had grown exponentially, by nearly 1000%, over the war years from £0.65 billion in 1914 to £7 billion in 1918. The interest on this alone represented about 8% of GDP.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_British_national_debt.

Though these numbers sound quaint today, this is why it’s said “All Wars are Bankers Wars”.

“Pittman Act“

The Act’s sponsor, Senator Key Pittman from the mining state of Nevada, who trained as a lawyer, had worked as a miner for four years in the Klondyke gold rush. His brother Vail Pittman worked in mining and was a mine owner. He went into politics and ultimately becoming Governor of Nevada. So mining was in the blood of Senator Pittman. Nevada calls itself the ‘Silver State’ because of the significance of silver production.

From Wikipedia: Under the Act, 270,232,722 standard silver dollars were converted into bullion (259,121,554 for sale to Great Britain at $1.00 per fine ounce, plus mint charges, and 11,111,168 for subsidiary silver coinage), the equivalent of about 209,000,000 fine ounces of silver. Between 1920 and 1933, under the Pittman Act, the same quantity of silver was purchased from the output of American mines, at a fixed price of $1 per ounce, from which 270,232,722 standard silver dollars were recoined. The fixed price of $1 per ounce was above the market rate and acted as a federal subsidy to the silver mining industry.

“tremendous prices“

OTAGO DAILY TIMES, 28 AUGUST 1920, PAGE 6

THE RISE IN SILVER AND THE INDIAN EXCHANGE

The market price of silver went up to ~USD1.1* by the end of 1918, so India was paying a premium of 10% over what they were paying the United States under the Pittman Act.

* www.silverprice.org

MANAWATU TIMES, 30 APRIL 1921, PAGE 8

AMERICA’S AID TO BRITAIN.

“enormous amount of treasure“

Before the war global silver production was in the order of 200 million ounces.

“secretly sold“

Despite American newspapers knowing about it.

“left Britain owing“

OTAGO DAILY TIMES, 28 AUGUST 1920, PAGE 6

Though Britain claimed the balance of a war loan amounting to £66 million was due from India (DOMINION, 9 JANUARY 1918, PAGE 4).

“the population’s understanding of“

A prominent New Zealand politician of the day, John A. Lee, described the electorate as*

pronouncedly conscious of monetary theory…

Lee, J.A., “Simple on a Soapbox”, Collins Publishers, Auckland (1963) p133.

* Lee was describing the electorate after the 1935 depression period but there is no reason, based on the content of newspapers of the day, to believe this wasn’t the case in 1920.

Despite a sector boom in agriculture, New Zealand, like the other war belligerents, experienced high inflation during the war, and this continued in the early post-war years peaking in early 1920. Private debt increased significantly over this period too, and interest rates were rising. For example the Bank of New South Wales increased its New Zealand advances from £3.2 million in December 1914 and £5.3 million in December 1920, and they were not the worst example*.

* Sinclair, K. and Mandle, W.F., “OPEN ACCOUNT: A History of the BANK OF NEW SOUTH WALES in New Zealand 1861 - 1961”, Whitcombe & Tombs Ltd., Wellington (1961) pp171-174.

“shilling's worth of silver“

EVENING POST, 15 DECEMBER 1920, PAGE 9

“debased to 50% silver“

Australia continued to mint 50% silver coinage for circulation until 1963 (1964 for the threepence), though they produced a circulating legal tender 80% silver fifty cent coin when they changed to decimal currency in 1966. That coin served as a swansong to silver coin in Australia as it was the last circulating silver coin minted. They didn’t remain in circulation for long. By mid-1968 the price of silver had more than doubled and, in a manifestation of Gresham’s Law, many disappeared into peoples drawers, chests or safes as the copper nickel version appeared.*

* Over 36 million 1966 fifty cent coins were minted, which maybe explains why they are easily obtained on the numismatics markets, and generally sell with a small premium over the silver price. Ebay 1966 50 cent, Trademe 1966 fifty cents

EVENING POST, VOLUME CXI, ISSUE 97, 27 APRIL 1931, PAGE 8

SILVER COINAGE, LETTER TO THE EDITOR

DOMINION, 2 JULY 1931, PAGE 10

PARLIAMENT IN SESSION, SILVER & COPPER COINAGE. PROFIT IN MINTING

Fascinating (and new to me) story of the Pittman Act of 1918 and how the US bailed out Britain's 'India problem' vis-a-vis silver. One of many goofy capers the Brits got themselves into around WWI, the beginning of the end of their empire.

Great use of primary sources as well.

It would take me a while to go through that properly but, excuse the pun, you have done a sterling job! That is an impressive article at first glance and makes good sense.

I consider that the bankers, essentially German Jews by extraction, used the USA to further their aims to extricate as much wealth as they could from the UK and its dominions at the time.

Wars were a good way of seeking to bankrupt the country.