NZ Financial Resets: Part 2: 1914 - Gold Confiscation

Criminal theft: banknotes made legal tender; in practice gold confiscated from citizens (unannounced); in practice New Zealand population off the gold standard (unannounced)

“O Gold! I still prefer thee unto paper, which makes bank credit like a bark of vapour” ― Lord Byron.

“The desire of gold is not for gold. It is for the means of freedom and benefit” ― Ralph Waldo Emerson

“Money is gold, nothing else” ― J.P. Morgan testimony to Congress, 1912.1

Next: Who Stole the Silver?

Previous: Introduction

Home: New Zealand’s Financial Resets

New Zealand’s Financial Resets

PART 2: 1914 - Gold Confiscation

While some New Zealanders are aware that US President Roosevelt made an overt confiscation of US citizens gold in 1933, the now infamous Executive Order 6102, the confiscation of gold by the New Zealand Government in 1914 is almost completely unknown. This essay, the second in a series that examines the repeated theft of New Zealanders wealth and property by the Government, will present the evidence that it has stolen our gold, albeit covertly, using lies, war and time to hide the theft.

Banknotes No Longer as ‘Good as Gold’

Before the first world war private banknotes were essentially claims for legal tender specie (gold or silver coin), which were payable in specie, to the note bearer, on demand. This was sometimes called receipt money.

… customers receiving cash over the counter could demand gold or notes according to their convenience.2

The smallest denomination banknote, one pound (£1), was redeemable for a gold sovereign (0.2354 troy oz of pure gold), or 20 shillings (totaling 3.361 troy oz pure silver). In other words, the money system was a bi-metallic weight based system where 1 troy oz of pure gold was worth ~14 troy oz pure silver.3

In the lead-up to war, the gold reserves on which credit depended were inadequate for the world-wide expansion of industry stimulated by war fever. More credit means more banknote issue, secured mainly with bullion (gold, silver to a lesser extent). Consequently many nations, especially the belligerents, were stockpiling bullion, and people began hoarding gold. In London, there was a ‘run’ on the Bank of England as people rushed to exchange banknotes for gold. They obviously did not believe banknotes were as good as gold.4

In New Zealand, as hostilities commenced, the Government legislated banknotes as legal tender with banks no longer required to redeem their notes for gold. The only way Government got away with not calling this a confiscation was by saying it was a temporary war measure. This was a long way from the earlier requirement that banks5

note issue was not to exceed the amount of coin [i.e. gold and silver specie], bullion and public securities that it held in New Zealand, nor three times the coin and bullion.6

Banknotes could now be offered (tendered) for any debt and, though they could be refused, now the debtors offer of banknotes settled the debt. There was no legal recourse to recover the debt in another payment form, or retrieve goods, if banknotes were unwanted. It was an action to make a mafia don blush; people forced to accept paper in exchange for their labour, goods, or services, with no remedy if paper notes were unwanted.

But war distracts. The politicians had assured this was only a temporary war measure, and people were being told the war would be over by Christmas (i.e. 4 months away). So there was little initial public dissent from the business community or spending public, though there was some propaganda and a not so subtle appeal to patriotic guilt in the Christchurch Press during the war to encourage people to hand in their gold (“hoarding” is used as a pejorative here). Did this imply some public discord?7

MY LAST SOVEREIGN. A HOARDER'S FAREWELL.

A correspondent has declared that people are still hoarding gold coins, and that it is their urgent duty to exchange them at any bank for Treasury notes. My conscience is pricked, old boy, We must part…What memories you bring old boy…So, good-bye, old Last of the Magnificents! You must go. It would never do for some grandchild to find you, years hence, in an old bureau, and ask you sternly, "What did you do in the great war?" Your face, old boy, would not keep this honest golden hue—it would turn bilious yellow.— London "Daily Mail."…PRESS, 19 MAY 1917, PAGE 10

Objections did filter into the press even as late as 1920.8

New Zealand was not the only jurisdiction to make this ‘temporary’ change to the legal status of banknotes at this time. Other jurisdictions reverted back after the war to on-demand exchange for specie, but in what New Zealand’s central bank, the RBNZ, called “a sign of the growing independence” and reflecting “a change in thinking about currency” the gold standard was not reinstituted in New Zealand. That is, the New Zealand economy was being used as an experimental subject.9

Political Lies and Narrative Control

There can be no doubt the ‘temporary’ nature of the legal tender status of bank notes was a feint; it was always intended to be permanent. The enabling law, the Banking Amendment (No. 4) Act 1914 was enacted on 5 August 1914 with the Proclamation of details gazetted on the same day. Representative of the press coverage, in what looks like crude propaganda and an attempt to gain control of a narrative, the Christchurch Press commented (emphasis and [ ] added)10

When the Minister of Finance on July 21st [1914] introduced the Banking Amendment Bill, the political sky was clear, and the financial outlook free from any cause for anxiety. Even when he moved the second reading a little more than a week ago, he was able to say that it was being dealt with at a time when all the conditions were quiet and favourable, so that it might be placed on the Statute Book ready for any emergency that might arise. No one thought at that time that the step taken would so soon be justified. It is fortunate that the Bill was not brought down as a panic measure, but that time was available for its full consideration by the Public Accounts Committee.

The Christchurch Press continued with an appeal to the superiority and security of the Mother Country (emphasis added)

…it places the notes of banks doing business in New Zealand on the same footing as Bank of England notes occupy in England, which are legal tender everywhere except—and this is an important exception—at the bank itself, which is bound to give gold for its notes on demand.

Elsewhere in the same edition of The Christchurch Press11

The matter was, at the request of the Minister of Finance … made a matter of urgency, but as the Minister explained, this was not because of any scare, but to get the Bill out of the way. As a matter of fact, the Bill was prepared and introduced into Parliament before there was any news of the present international war trouble.

In the spirit of ‘everything they say is a lie’ familiar to alert mainstream media consumers today, this story is framed as business as usual when in fact the Government was acting in a state of exception. They were covertly stealing peoples property.12

“No one thought”? By late July 1914? Given a potential European war had been boiling loudly for months, and simmering for years — plus war had already been declared, at best this is a naïve statement. Obviously the Minister was dissembling. The Bill had been introduced into Parliament for its first reading two weeks before Britain declared war against Germany. Clearly conditions were not “quiet and favourable.”13

The statement that the Bill was “prepared and introduced … before there was any news of the present international war trouble” was a lie. With Standing Orders suspended and parliament placed in urgency to pass the Act, did readers believe any of this? The British declared war on 4 August; given the time difference New Zealand’s Banking Amendment (No. 4) Act must have passed almost simultaneously.14

Furthermore, the banknotes were not “on the same footing as Bank of England notes;” this was a provable lie at the time. New Zealand did not have a central bank in 1914. Banknotes were issued by private banks and these notes were not redeemable in specie by the issuer, or any other entity, in any circumstance, while the Banking Amendment (No 4) Act 1914 and proclamations under it were in place.

Why the propaganda and lies? Maybe to quell the immediate disquiet at what was an obvious theft, and concerns over the stability of paper currency. Even ex-prime minister and leader of the opposition Sir Joseph Ward got in on the act.15

Sir Joseph Ward, speaking on the third reading of the Bill, said that he thoroughly agreed with the proposals made by the Government. He also agreed with the views expressed by the Prime Minister and the Minister of Finance that there was no occasion for anxiety on the part of the people of this country. Even in ordinary times the provision now being enacted was, in his opinion, a wise thing … THE BANKING BILL. OTAGO WITNESS, 12 AUGUST 1914, PAGE 13

The opposite of the truth. The more things change the more they stay the same.

The initial Proclamation was only valid for a month, expiring on 6 September. A further Proclamation was gazetted two months after the first, on 5 October, expiring three months later on 7 January 1915. The month long interval where redemption in specie returned would have served to allay concerns that irredeemability was permanent. The 5 October Proclamation suspended redeemability again, this time for three months. By 7 January 1915 most people would have been in a state of war fever. The Government started creating currency hand over fist, via debt , to fund war. Publicly, money issues were conveniently forgotten.16

This proclamation process was recycled until 1931. As the authors of the history of the Bank of New South Wales recognised, referring to events over a generation later “As is unfortunately common, wartime emergency measures persisted after hostilities ceased.“ The ‘temporary’ 1914 Act was finally repealed in 1934, twenty years after it was first passed.17

Cui bono?

Who benefited from the 1914 law change?

In practice, the gold became the property of the banks. Banks couldn’t easily sell the gold on the international market because gold exports were prohibited without approval by the Finance Minster. But it did allow the banks to expand their note issue, a source of profit because of seigniorage and because18

… the value to a bank of the right of issuing notes was ‘the advantage of additional capital for which it pays nothing'19

Banknotes still needed to be backed by assets, and specie coin and bullion were both important assets at that time.20

Before making any such Proclamation the Governor in Council may require that adequate security be given by the bank for the performance of the condition that the bank shall pay all such notes of its own issue in gold on presentation at the office of the bank at the place of issue of the said notes respectively after the expiration of the period limited by any original Proclamation under this section, or by successive Proclamations thereunder if more than one. … Banking Amendment Act (No. 4) 1914, Section 2(3)

This key section is the smoke and mirrors which gives the appearance of security. Section 5 gives the game away

Upon the request of the Minister of Finance the managing director, manager, or accountant of any bank shall make full and true answers to such written inquiries concerning the business, and the assets and liabilities, of the Bank as the said Minister thinks fit to make for the purpose of the exercise of the power conferred on the Governor in Council by section two of this Act, and shall verify the same by his statutory declaration…Banking Amendment Act (No. 4) 1914, Section 5

There were no independent auditing requirements on banks in the Act. Only a requirement for banks to “make full and true answers” if the Minister enquires. The Act’s implementation was dependent on the honesty of bankers and politicians. Not a good start. The banks benefited enormously from the new law.

Holders of banknotes were obviously the most seriously negatively affected; their gold (their property, their money) was confiscated, though it was unannounced and the owners didn’t know it at the time. On 5 August 1914 New Zealand effectively went off the gold standard, also unannounced and unacknowledged. Aside from being a criminal theft, it was the first stage in removing the idea of gold as money from the consciousness of New Zealanders. We had taken a big step, unseen by the public and obfuscated by the political class, towards a debt based fiat currency system.21

By 1914 the New Zealand banking system was well developed, with six major banks in operation throughout the country. Those with the financial resources to have large hoards of gold and silver used the banks to secure their wealth. Banknotes had been used for many years and were generally trusted. That said, because of their high purchasing power, neither banknotes, nor the sovereigns they stood for, were used for everyday transactions. Sovereigns may have been withdrawn for higher value purchases, or for travel, but when the transaction was large and local, banknotes were trusted and probably preferred for settlement of debt.22

Consequently the 1914 law change did not directly or immediately affect most people in their daily lives. The majority of consumer transactions used, and most people were remunerated with, the other legal tender currency, silver specie coin (legal tender coin being British, 92.5% sterling silver for denominations 3p and above, copper or bronze for lower denominations). But the Government was coming for the silver next.

Next: Who Stole the Silver?

Previous: Introduction

Home: New Zealand’s Financial Resets

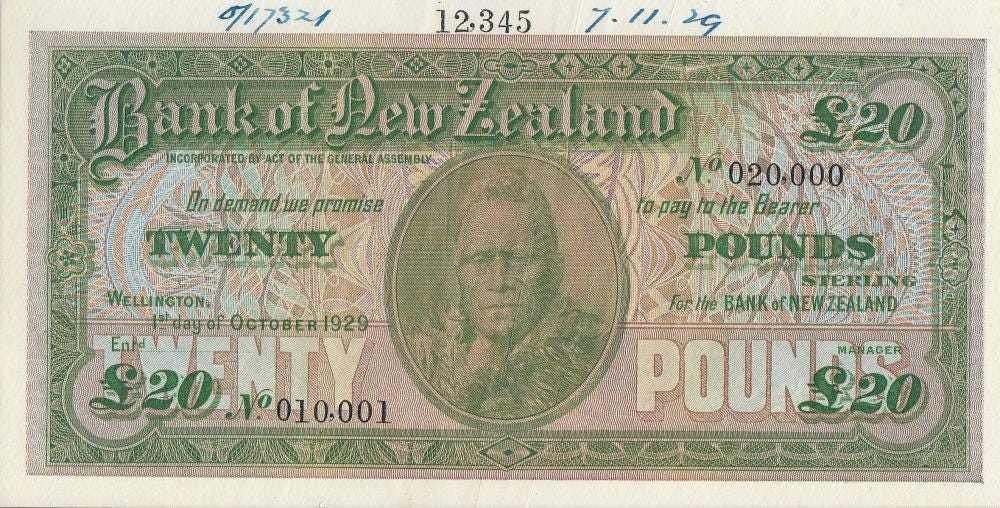

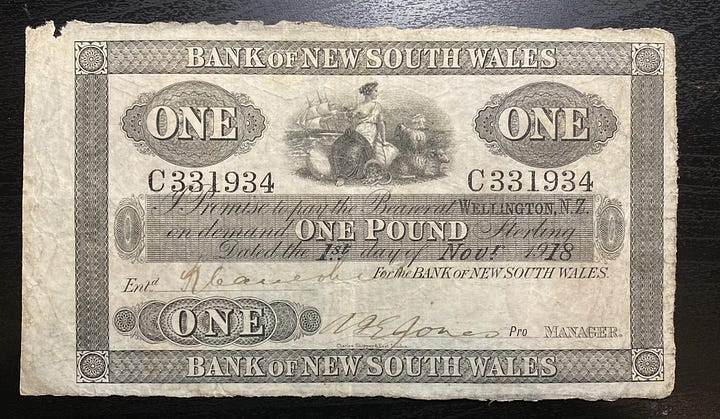

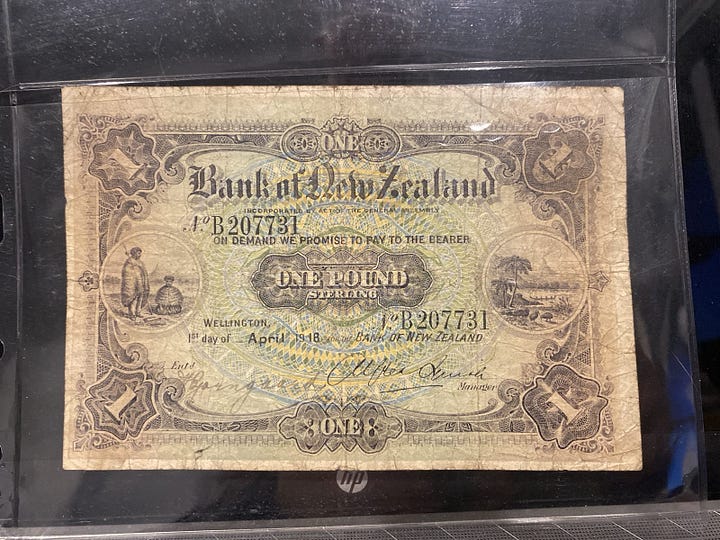

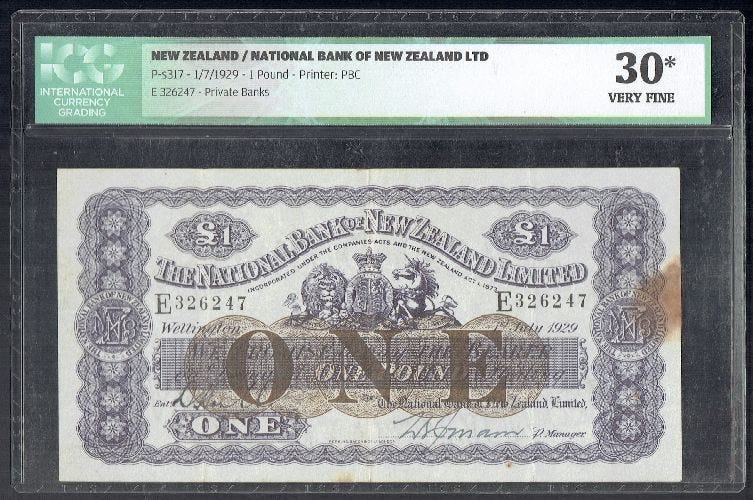

APPENDIX 1 - PRE 1914 BANK NOTE EXAMPLES

See also: https://en.numista.com/catalogue/nouvelle-zelande-banknotes-1.html#c_nouvelle-zelande217

APPENDIX 2 - POST 1914 BANK NOTE EXAMPLES

APPENDIX 3 - SOME EARLY BANKS IN NEW ZEALAND

Image references in footnotes.23

Testimony of J.P. Morgan Before the Bank and Currency Committee of the House of Representatives, at Washington D.C. Appointed for the Purpose of Investigating an Alleged Money Trust in “Wall Street”, December 18 and 19, 1912. p 48. Source.

Chappell, N.M., “New Zealand Bankers Hundred: A History of the Bank of New Zealand 1861 - 1961”, Bank of New Zealand (1961), p278.

“smallest denomination banknote“

This changed in 1916 after gold half-sovereigns stopped being delivered by the Australian mints, and the BNZ received permission from the Government to produce a ten shilling note (equivalent to a gold half-sovereign) to “save a drain on silver coin”, which they did immediately.*

* Chappell (1961), p278.

British specie silver coin (3 penny, 6p, shilling=12p, florin=24p. half crown=30p, crown=60p) produced before 1920 consisted of 92.5% silver and weighed 5.65 gram = 5.2g silver per shilling. e.g. https://en.numista.com/catalogue/pieces4717.html

20 x 5.2 = 104.5g / 31.1 g/troy oz = 3.361 troy oz. So the gold to silver ratio was 0.2354oz Au = 3.361oz Ag ~ 14:1.

Technically it was a tri-metallic system, because copper or bronze (~88% copper, 12% tin) coin was used for the lowest denomination coins (1 penny and below).

“Consequently many nations“

Chappell (1961), p277.

“a ‘run’ on the Bank of England“

FINANCIAL AFFAIRS. WANGANUI HERALD, ISSUE 14361, 3 AUGUST 1914, PAGE 6

A RUSH FOR GOLD. BANK OF ENGLAND’S PRECAUTIONS. LONDON, July 31, 1914.

After receiving notes from other banks crowds invaded the Bank of England and exchanged the notes for gold. The Bank will probably take steps against gold being secured in this manner for transmission abroad.

The Banking Amendment (No. 4) Act 1914 was passed 5 August 1914. It was finally repealed with the passing of the Finance (No. 3) Act 1934, for 1935 enactment.

In the first two years of war gold coin issue was not absolutely prohibited, and gold half-sovereigns remained in limited circulation. Half-sovereigns were minted in Australia, and deliveries ceased in 1916 when gold exports from Australia were prohibited.*

* Chappell (1961), p278.; Hargreaves, R.P., “From Beads to Banknotes”, John McIndoe Limited, Dunedin (1972), pp134-135

Sinclair, K. and Mandle, W.F., “Open Account”, Whitcombe & Tombs Limited (1961), p27. Open Account is a history of the Bank of New South Wales in New Zealand from 1861 - 1961.

"over by Christmas"

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers?sort_by=byDA&items_per_page=10&snippet=true&query=%22over+by+Christmas%22&start_date=01-08-1914&end_date=31-12-1914

[ADDENDUM: The following will be added to over time]

The banks had this to say ([] added):

“the object was to strengthen [the banks] still further and to allay any feelings of public nervousness arising from the shock of war.“ Chappell, N.M., New Zealand Banker’s Hundred - A History of the Bank of New Zealand 1861-1961, Bank of New Zealand, Wellington (1961) p277.

LEGAL TENDER NOTES. PRESS, VOLUME LVI, ISSUE 16979, 30 OCTOBER 1920, PAGE 10

Sir,—”De l’audace, de l’audace et toujours de l’audace!” There is nothing better than audacity when a man. knows that he is right. But what right or authority has Mr Massey for saying that bank notes "will be legal tender for quite a long time to come"? How much longer does Mr Massey suppose that we shall submit to a forced currency of private bank notes? Or to have our gold locked up and hoarded in the banks? At present the date expires on December 31st, 1922. Will Mr Massey give permission to the banks to increase the amount of the note circulation, which is now nearly eight millions?

“No person is allowed to coin any token to pass for, or as representing, bronze or other money under a penalty of £20.” In 1845, Captain Fitzroy was dismissed from the Crown Governorship of New Zealand because he had issued Treasury notes of 5s each and upwards, to less than the amount of £40,000, and had made them legal tender. It was contrary to the British Constitution. What right, then, had the Dominion Government to make millions of private bank notes legal tender; and to guarantee them; or to allow the banks to lock up our gold? Clearly, if the Government makes notes legal tender, and guarantees them, the Government ought to issue the notes and hold the gold reserves. Long ago, when the note circulation of New Zealand was less than two millions, Sir Robert Stout admitted that it was the duty of the Government to issue notes, and that if it did so, it would be equivalent to a loan from the people to the Government free of interest. This is what is done now in Australia, and the British Government has issued some £260,000,000 of legal tender Treasury notes of £1 and 10s each—or higher notes. "What right has Mr Massey, or his Government, or the Parliament, or even the Governor-in-Council, to make private bank notes, “promising to pay pounds sterling on demand,” legal tender instead of gold— or State or Treasury notes? What right has Parliament to give the banks the equivalent of a loan of nearly eight millions at 3 per cent interest (the rate of the note tax)? Or to allow the. banks to hoard up uselessly several millions of coin—which, according to Mr Massey's dictum, will not be required "for quite a long time to come"? According to British law, Mr Massey could not give the right to any person to coin a single penny bronze token! How absurd then, to suppose that he could give private banks the right to issue millions of one pound notes—and call them sterling! I sent this letter to another paper on September 30th, and have written twice enquiring why it was not returned if refused, as I had, as usual, enclosed stamp. But "The Press" professes to be "always ready to give publicity to any question in its correspondence columns," so I hope you will publish this without delay. The Bank of New Zealand wants silence!— Yours, etc., J. MILES VERRALL. Swannanoa, October 38th, 1920.

“Other jurisdictions reverted back“

Eventually and at different times. No gold standard lasted, and at different times countries took themselves off their gold standards. For example the U.S., which did not go off their gold standard with gold coin circulating domestically until 1933. The U.K. on the other hand took gold out of circulation and went off the gold standard in 1914, returned to a different gold standard in 1925—including without circulating gold coin. It failed in 1931 and British currency became fiat.

PRESS, VOLUME L, ISSUE 15038, 5 AUGUST 1914, PAGE 8

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19140805.2.55

PRESS, VOLUME L, ISSUE 15038, 5 AUGUST 1914, PAGE 9

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19140805.2.65

Not only was the Government acting in a state of exception, the expropriation was contrary to international law going back nearly 200 years.

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand was at best a proximate trigger, or justification, for the first world war. For a comprehensive analysis of the planning and multi-decade long buildup to the war see https://www.corbettreport.com/wwi/.

“already been declared“

The official timeline of the declarations of war was published in 1932 in the King Country Chronicle.

DECLARATION OF WAR, King Country Chronicle, 6 August 1932, Page 5

PRESS, VOLUME L, ISSUE 15040, 7 AUGUST 1914, PAGE 15

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19140807.2.201

This action must have been very controversial; ideas about money, gold, silver, currency, banknotes, and legal tender were actively debated topics in early 20th century New Zealand society, as a search of Past Papers shows. But there is barely any critical reportage or correspondence in newspapers at the time, and a real critique only begins to appear after 1918.* The news cycle quickly moved on and the next day’s press was full of war news e.g. Christchurch Press, 6 August 1914. Which is why major financial resets always happen in conjunction with a major crisis such as war.

* An example from the EVENING POST, 9 FEBRUARY 1921, PAGE 7, the writer acknowledging the gold sovereign is probably gone for good.

The new coins are from the same dies and are dated 1920. They will presently be in circulation in New Zealand. Those who receive them will be able to compare them with the older silver, and possibly feel that the return of the sovereign or welcome "yellow-boy" seems farther off than it ever was before.

“The initial Proclamation“

The New Zealand Gazette Extraordinary Issue 74 pp3043-3044 (5 August 1914)

The New Zealand Gazette Extraordinary Issue 107 pp3693-3694 (5 October 1914)

Notes from the the six trading banks were made legal tender with the first Proclamation: The Bank of New Zealand, The National Bank of New Zealand, The Union Bank of Australia, The Bank of Australasia, The Bank of New South Wales, The Commercial Bank of Australia.

“Government started creating currency“

An estimate of the growth of Government debt can be obtained from newspapers of the day. The numbers mentioned vary slightly, and have not been verified with official figures, but certainly give an idea of the growth pattern:

1912: ~£82 million - SUN (CHRISTCHURCH), 30 NOVEMBER 1914, PAGE 6

1914: ~£92 million - SUN (CHRISTCHURCH), 30 NOVEMBER 1914, PAGE 6

1917: ~£125 million - GREYMOUTH EVENING STAR, 4 SEPTEMBER 1918, PAGE 4

1912-1914 (2 years) = +12%

1914-1917 (3 years) = +47%

“…of the total New Zealand [government] war loans of £82,000,000, some £55.000,000 were raised within the dominion.” Butlin, S.J., Australia and New Zealand Bank, Longmans, Australia (1961), p 361.

“proclamation process“

For example

In 1925 the notice appeared fixing the expiration date as January 10, 1927 … However in November last a further notice appeared making bank notes legal tender till January 10, 1928; and it seems quite probable that a further extension may then be granted. - SOUTHLAND TIMES, 8 JANUARY 1927, PAGE 6

The final banknote Proclamation under the Banking Amendment (No. 4) Act was in the New Zealand Gazette, No 77, 22 October 1931.

“unfortunately common“

Sinclair and Mandle (1961), p214.

“finally repealed“

With the passing of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act 1933, and its final coup de gras the passing of the Finance (No 3) Act 1934.

I haven’t yet identified any legal mechanism but I doubt there was legislation transferring legal title to the banks, a step that would likely have caused an uproar*. Given banknote legal tender proclamations under the 1914 Banking Amendment (No. 4) Act continued until 1931 it looks like this question was left in limbo.** Ultimately the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act 1933 resolved the question by transferring all gold ownership from the banks to the new, initially privately owned, Reserve Bank of New Zealand. The banks were certainly the ‘beneficial’ owner of the gold; because of seignorage, issuing banknotes is a profitable business***, even with the 2% per annum tax**** paid to the Government.

__________

ADDENDUM

The gold ownership issue continued to come up. While celebrating the resumption of gold exports by Britain, a writer for the ASHBURTON GUARDIAN, 2 MAY 1925, PAGE 6 felt

It seems certain that the banks…have no intention of redeeming their notes in gold on demand.

An editorial in 1930 the Dominion was unequivocal

[The banks] are the owners of the gold, and can quite properly regard its disposal as their own business…DOMINION, 4 SEPTEMBER 1930, PAGE 8

While the same paper a week later, discussing the “wobbling money,” almost mournfully reflected

We never see [gold] sovereigns nowadays in any case…DOMINION, 11 SEPTEMBER 1930, PAGE 7

In late 1933 when the Reserve Bank Bill was in its final stages, the Chairman of the Associated Banks, Mr. J. T. Grose, stated

“This gold was purchased with the banks’ own assets, and was, and is, as undeniably their own property as are their premises. To take this gold at anything less than its real value would be straight-out confiscation…KING COUNTRY CHRONICLE, 19 OCTOBER 1933, PAGE 5

When the Reserve Bank Act (1933) was passed on November 3 1933. [ ] added.

A POLICY OF EXPROPRIATION

…Sir Francis Bell has given his opinion that, in law and in fact, the gold is the private property of the banks. Could anything be more obvious? It requires no enunciation of legal principles to support Sir Francis Bell’s assertion. The whole facts of the case trumpet the truth that the gold is the private property of the banks. The gold has been imported into the country by the banks [not true; originally it was confiscated in 1914]; it has been regarded for the purposes of taxation as the property of the banks; it has stood at the risk of the banks, in that if it had been lost through earthquake or burglary the Government was under no obligation to replace it; the New Zealand Gazette publishes quarterly a “Statement of the Liabilities and Assets of the Undermentioned Banks.” in which the gold coin and bullion is shown as an asset of the banks, while even the draftsman of the Reserve Bank Bill can find no language appropriate to the Bill itself but that which admits the gold to belong to the banks in question, for the Bill speaks of the “gold coin or bullion then held by it (the banks) on its own account.” …PAHIATUA HERALD, 4 NOVEMBER 1933, PAGE 2

By the time the Reserve Bank was opening its doors in 1934 (emphasis and [ ] added)

The [New Zealand] banks argued that since the gold coins were their own absolute property

Hargraves, R.P., From Beads to Banknotes-The story of money in New Zealand, John McIndoe Ltd., Dunedin (1972) p 165.

__________

* Though as early as a week after the new law one reader of the Christchurch Sun, believing that the gold had already “really” been confiscated, in a fit of patriotic fever called for it to be shipped to England!

All this gold really belongs to the government and people of New Zealand … GOLD FOR ENGLAND. SUN (CHRISTCHURCH), 11 AUGUST 1914, PAGE 6

** A. N. Field in a 1933 article in the Nelson Evening Mail discussing the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bill and the potential sale overseas of the gold held in New Zealand banks states

This gold, however, is not the property of the people of New Zealand, but of the trading banks … RESERVE BANK BILL, NELSON EVENING MAIL, 30 JANUARY 1933, PAGE 8

*** Chappell states there was “no extra profit” from issuing, in the case of the Bank of New Zealand, an extra £600,000 “immediately” due to the note tax and the cost of “maintaining the swollen note supply”. I think the keyword here is “extra”.

Chappell (1961), p278.

**** See below

For this privilege of note issue there is levied on the banks a tax of 2 per cent, per annum. … NEW ZEALAND TIMES, 10 SEPTEMBER 1914, PAGE 7

By 1920 the banknote tax had increased to 3%.

What right has Parliament to give the banks the equivalent of a loan of nearly eight millions at 3 per cent interest (the rate of the note tax)? … LEGAL TENDER NOTES. PRESS, 30 OCTOBER 1920, PAGE 10

Chappell states “the banks paid a tax of 3 per cent” and “the note tax was increased later as part of war taxation.” Chappell (1961), p278-279.

See the New Zealand Gazette under “Statement of the Liabilities and Assets of the Undermentioned Banks.” published quarterly.

Gold was exported when the ban was in place. For example the Bank of New South Wales in March 1932.

It received permission to ship £150,000.

Sinclair and Mandle (1961), p205.

Sinclair and Mandle (1961), p29.

BANKS AND GOLD RESERVES, HAWERA & NORMANBY STAR, 3 JANUARY 1914, PAGE 4

Sir Edward Holden, chairman of the London City and Midland Bank, recently gave an address on banking and gold reserves … By means of a triangle with two equal sides, he showed what the business of a bank really is. The right side of the triangle he likened to debit balances and the left side to credit balances. So long as confidence existed a banker might increase his loans ad libitum, which meant that the right side of the triangle might be elongated indefinitely. If, therefore, the loan or right side of the triangle were elongated the credit or left side of the triangle must also be elongated, and vice versa. But in the building up of the two sides, the banker must be careful to extend the base (which represents gold and other liquid assets) of the triangle also. Should a crisis came, in all probability customers might want gold, and therefore it was of the greatest importance that every banker should hold a certain proportion of gold. He denied the allegation that bankers did not hold gold, and asserted that on the contrary they held a large amount. In order that the critics might be satisfied that a proper proportion of gold was held, and that the proportion would be increased as the two sides of the triangle were increased, the proposition had been made that bankers should disclose in their balance-sheets at least once a year the amount of gold which they held. As. a matter of fact the Bank of England held gold to the value of nearly £36,000,000 as part cover for the notes in circulation, and this gold constituted the national reserve of the precious metal. It did not represent the whole stock of gold in the country for the joint stock banks held a large amount …

“effectively went off the gold standard“

Two issues here. Some argue that technically, because of the fixed exchange rates, New Zealand went back on the gold standard when Britain went back on the gold standard in 1925. This was a gold standard for nations and banks. Not the population. Gold was not in circulation.

NEW ZEALAND HERALD, 4 JANUARY 1926, PAGE 5

BANKING IN NEW ZEALAND. NOTE ISSUE AND EXCHANGE.

…Exchange difficulties were removed, however, by the return to the gold standard. New Zealand went back to the gold standard officially on April 29 last, simultaneously with Great Britain and Australia, In the case of New Zealand, however, the legislative restrictions were not removed outright and the Government still maintains a control over the movements of the metal."

It is also argued New Zealand came back on the gold standard in 1944 with the Bretton Woods agreement. I disagree. Bretton Woods fixed all currencies to the US dollar (USD), and the USD was fixed to 1/35 troy oz of gold (i.e. the gold price was US$35 per troy ounce). The problem was the US could (and did) expand the USD supply ad infinitum. Countries could buy USD at the fixed exchange rate, and then sell USD for gold. Again, gold was not in circulation.

“were generally trusted“

Banknotes had been used since earliest settlement in New Zealand. The first bank in the colony, the Union Bank of Australia, partnered with the New Zealand Company and arrived simultaneous with the first settlers. It opened its first branch in 1840 in (what is now) Wellington, and began issuing banknotes to settlers immediately. By March 1841 they had issued notes valued at £4415* and by 1846 the Nelson branch had £7000 of notes in circulation, four years after opening there. In order to stimulate commerce, settlers in New Zealand made several attempts at private paper money and tradesmen issued tokens as small change. By the 1860s there were eight banks operating in New Zealand. The first local bank, the Bank of New Zealand founded in 1861, began issuing a banknote for £1 immediately.**

When banks began operating on the goldfields in the mid-19th century, they paid gold miners for raw gold with banknotes, making miners among the largest group of earliest users. Being much less weight than sovereigns it was easier for the miners to carry high value amounts on their person. Maybe the miners though they were managing risk, but banknote paper quality was varied, and sometimes the value disappeared in the rain. See George Preshaw, “Banking Under Difficulties”, 1888. I don’t know the extent that this was still practiced by 1914.

* Butlin, S.J., “Australia and New Zealand Bank”, Longmans, Australia (1961), pp153-155.

** Hargreaves (1972), pp25-53, 63, 80-90.

“preferred for settlement of debt“

Banknotes were preferred because they were more secure than sovereigns. Unlike sovereigns, which were essentially identical*, banknotes were uniquely identifiable from the serial number**, which was recorded by the issuing bank. If they were lost or stolen there was at least some chance of retrieval and remedy. Also sovereigns were heavier and bulkier than banknotes; greater purchasing power could be more easily carried on the person with the latter.

* in size, weight, lustre/sheen, and gold content. Mint location, date, and the obverse image differed, but there were still millions, sometimes tens of millions, of exactly the same coin.

https://en.numista.com/catalogue/index.php?e=royaume-uni&r=sovereign

** An example of stolen banknotes in 1903 reported in the New Zealand Herald.

The numbers of the notes are known, and the banks have been advised. The police hope to clear the whole matter up within a few days. CANTERBURY NEWS. NEW ZEALAND HERALD, 25 AUGUST 1903, PAGE 3

Left to right.

Top

1898 - Bank of New Zealand at Paeroa during the flood

1880 - Bank of New Zealand, Queen Street, Auckland Central

1892 - Bank of New Zealand, Queen Street, Auckland Central

Middle

1860s - Bank of Auckland, Princes Street, Onehunga

1870 - Bank of New South Wales, Lawrence

1880 - Bank of New Zealand, Cathedral Square, Christchurch

Bottom

1880s - Auckland Savings Bank and Edson's Buildings

1891 - Bank of Australasia, Patea

1899 - Bank of New Zealand, Hamilton West

As a preamble to this series, have you considered providing a brief history of money, with an explanation as to why a gold/silver standard is preferable to fiat and the ill effects of money supply expansion? Something along the lines of Rothbard in "What Has Government Done To Our Money" or "The Case Against the Fed?"

Reading part 3 now.

There's nothing so permanent as a "temporary" government program.