NZ Financial Resets: Part 4b: 1930 - Treasury Beguiles

Treasury blows up a balloon, and lets it go

“I may add that the establishment of a note issue board…might in due course form the nucleus of a central bank” - Mr. B. Ashwin Esq., 5 June 1930, Wellington, New Zealand.

Next: A Prussian’s Wiles

Previous: Central Bank Conspiracies

Home: New Zealand’s Financial Resets

Calls for a central bank in some form had been part of New Zealand discourse since the 1860s. In 1913 high interest charges led to a proposal in Parliament that a Royal Commission should be formed to investigate the banking system, with a view to establishing a new central banking institution.1

When Prime Minister William Massey attended the 1923 Imperial Economic Conference (IEC) in London the issue arose again; the IEC adopted the recommendations of the previous year’s Genoa Conference which included the creation of central banks. A year later Massey, answering a question in Parliament about the British - New Zealand exchange-rate, stated

…the best means of affording relief is through the operations of a central bank…this measure might be further developed and assisted by the creation of central banks…as recommended by the Genoa Conference."2

Nothing visible in the public discourse resulted, at least as represented by newspapers of the day. This changed in 1930.

First, a call for financial reform and a central bank came from an ‘insider’ who gave an important speech in early June in the capital, Wellington. Then later in the year a senior Bank of England (BoE) official, a financial expert who had previously been Controller of Finance at HM Treasury, visited New Zealand. He stayed a few weeks, gave a few speech’s, attended a few meetings and departed. In February 1931 his report was presented to the Prime Minister.

Two men fronted the initial operation to institute a central bank in New Zealand.

One was a senior Treasury official who soon became one of New Zealand’s most powerful men. The other had risen to the near-top of HM Treasury before moving to the Bank of England. He became a Director of the Bank for International Settlements, and ultimately Chairman of the Board; publicly, the most powerful banker in the world.

Part 4b of the New Zealand’s Financial Resets series, 1930 - Treasury Beguiles, is the story of the Treasury’s initiation of New Zealand’s central bank.

Treasury’s Trial Balloon

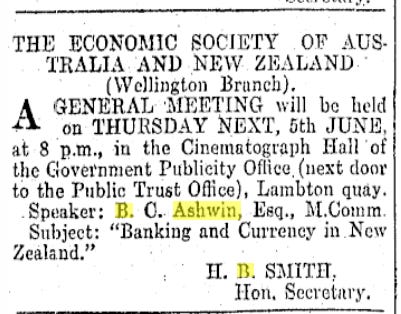

The 4 June 1930 edition of Wellington’s Evening Post carried an innocuous advertisement of several lines placed without prominence near the bottom of Page 2. It announced a meeting of The Economic Society of Australia and New Zealand (Wellington Branch) was to be held the next evening, and a B.C. Ashwin, Esq., M.Comm., was to speak on Banking and Currency in New Zealand.

As the effects of the depression was starting to grip the country it was apparent Banking and Currency in New Zealand was a popular subject because the next day’s Evening Post announced that, due to demand, that night’s meeting was relocated to a larger venue.

It may have been the subject matter that drew the unexpectedly large crowd. But it may have also been the speaker. Because Mr. B.C. Ashwin, M.Comm. was at that time a man of prominence in New Zealand’s political, financial and economic worlds. An audience in the nation’s capital would have known exactly who he was, and the significance of the topic he was addressing.

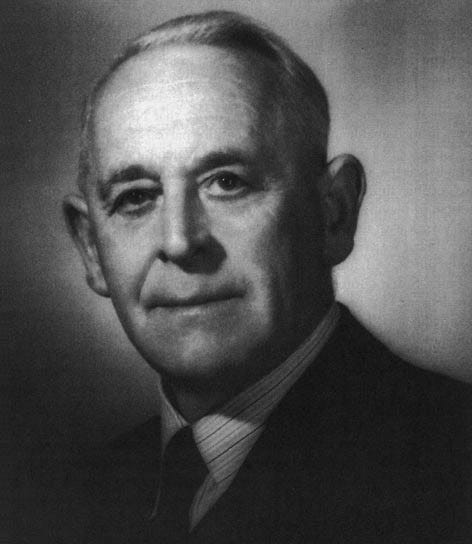

Treasury’s Point Man: Bernard Ashwin

By 1930 Bernard Carl Ashwin had been at Treasury for 8 years and on the night of 5 June held a senior management position; either Chief Inspector or Assistant Accountant. Either way, there was an interesting silence in this regard in the meeting notice. For the Economic Society and the Evening Post, the editor of whom without any doubt would have known who Ashwin was, it was plain Mr. Ashwin M.Comm. speaking. Why this subterfuge, this small deception? Was it for reasons of plausible deniability, in-case the proposals ultimately presented were received with too much hostility? Or maybe Treasury just wanted as little publicity as possible at the time? We can only speculate.3

The speech, despite Ashwin’s disclaimer to the contrary, was obviously done with the blessing of his colleagues including the Secretary to the Treasury, Alexander Park. It was likely also approved by senior politicians, and probably bankers. The speech appears to be what today would be called a trial balloon, and it was widely reported in the nation’s press over the next few days.4

Ashwin’s Speech - Banking and Currency in New Zealand

To describe the contents of Ashwin’s speech as dynamite is understating the implications of what was said, given who was saying it. Though it looks rushed - the public announcement gave one days notice - the speech’s substance was far from rushed. Ashwin was detailing the result of long- and careful planning. As mentioned above, it received wide coverage in the nation’s press; unsurprisingly the most detailed reports are found in the capital’s newspapers, the Dominion and Evening Post.5

It is worth examining the speech in some detail because what Ashwin proposed that evening was in substance what was eventually proposed by the Bank of England official less than a year later, and what would eventually be implemented by the government with the passing of the Reserve Bank Act (1933).6

Ashwin was expansive. He addressed New Zealand’s pre-war financial system, then the economic, financial, and legislative changes resulting from the war. He followed this with his analysis of the most pressing political and economic issue of the day, the exchange-rate with Britain, and offered suggestions for managing what was a deteriorating economic atmosphere.

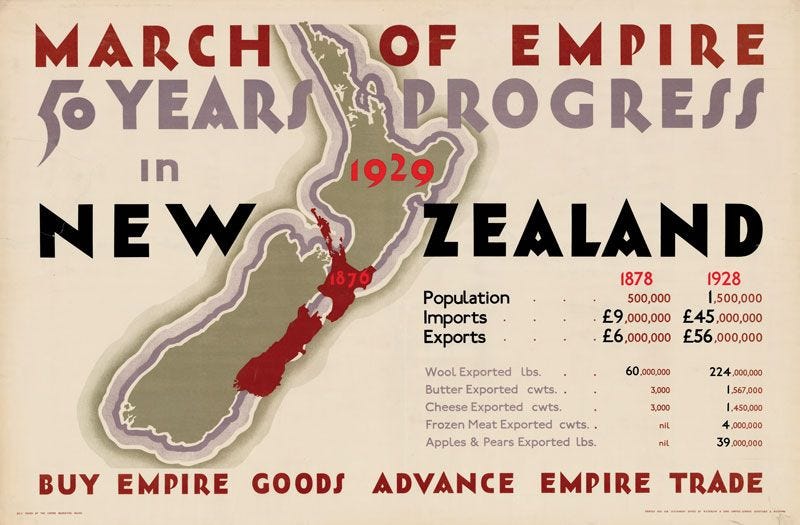

Most of New Zealand’s exports went to Britain. Nearly all our manufactured goods came from Britain, and all foreign trade was settled in London. So the British exchange-rate was one of the most influential elements affecting the financial health of New Zealanders.7

The exchange-rate was set independently by each bank, and was heavily dependent on the state of their London balances. As balances were a function of the trade balance, which showed a total surplus of £22,000,000 in the previous two years, it was believed the exchange-rate should, all things being equal, be close to the cost of shipping gold to London; about 1.5%.8

And in early 1930 the exchange-rate with Britain was 5%. This was good for exporters, who were the ultimate source of the national income, but not for importers of manufactured goods and their customers, the entire population.9

Ashwin identified where he thought the exchange-rate mechanism was faulty. Four of the six banks operating in New Zealand were “primarily Australian institutions” and they treated their London funds, used to finance the trade of both countries, as “one fund.” Australia had a “heavy adverse trade balance” and a “severe restriction of London borrowing”, and as a consequence their London balances were “practically exhausted.”

No wonder he spoke as Mr. B. Ashwin, Esq.; if someone with the imprimatur of the New Zealand Treasury had spoken these words publicly, diplomatic exchanges were surely guaranteed. Ashwin was arguing New Zealand was subsidizing Australia, in the form of a higher exchange-rate with Britain than was warranted by the New Zealand - Britain trade balance. He was also acknowledging something that was only then beginning to surface in public across the Tasman. The Australian banks were experiencing significant stress.10

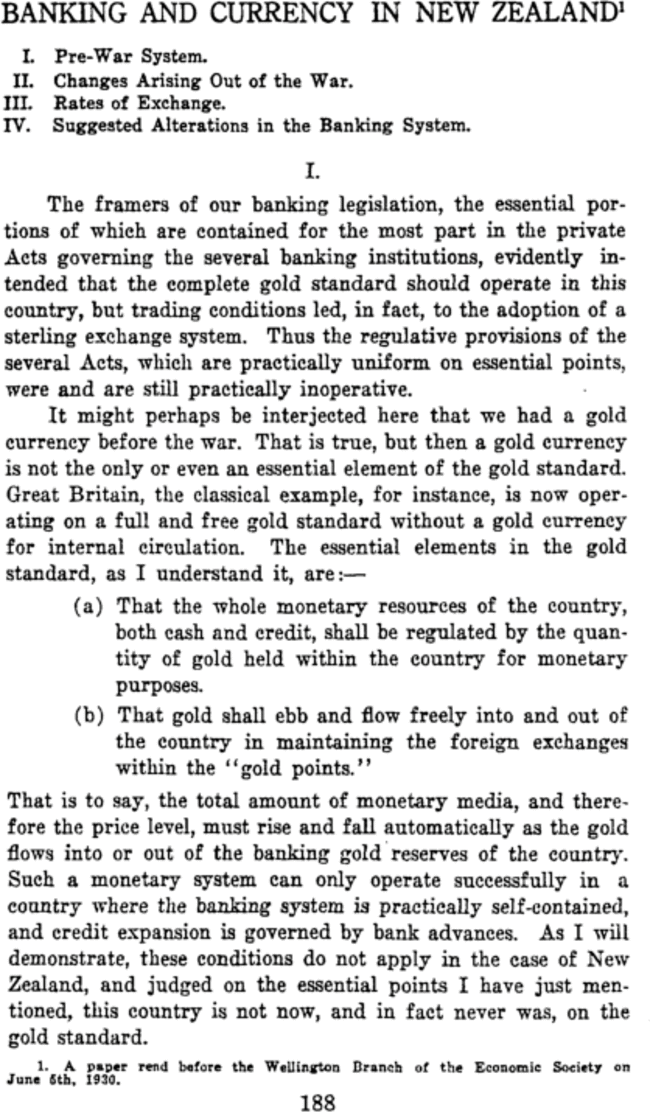

Ashwin characterised the current banking regulatory and legislative regime as unsatisfactory, having developed for a system operating under a gold standard when the actual system in place was a sterling exchange standard. He proposed that either the financial system needed to fit the existing legislation, which would be a return to a gold standard, or the legislation should be changed.11

Ashwin then argued for the legislation change to a sterling exchange standard which

would enable large savings to be made for the benefit of the people generally, and, incidentally, the Dominion was in need of savings at the present time.

And how was this magical benefit to “the people” and “the Dominion” to arise? Gold. New Zealand banks were to surrender their gold, gold that had been stolen from the population in 1914.12

His argument went something like this.

“For since by man came death,

by man came also the resurrection of the dead”

1 Corinthians 15:21

Channeling John Maynard Keynes, Ashwin went to some length to deface gold held in New Zealand. It held “no real economic significance, as a pound note does the work just as efficiently as a sovereign.” The banks held “£6.6 million of gold which had remained quite unused for any purpose in the vaults of the banks for the past fifteen years.” This gold was a “dead asset” costing the country £330,000 per annum. Ashwin proposed turning this gold into an interest earning asset, which he suggested would reduce the overdraft rate by 0.5% without affecting deposit rates or bank dividends.13

The gold was currently being held so banks would comply with the 1914 Banking Amendment Act, and Ashwin argued “that action should be taken without further delay to…make the necessary amendments to the present banking legislation.” To return to gold coin circulation “would be a pure luxury which this country cannot really afford“ and as gold circulation had practically ceased even in the gold standard countries it was safe to assume it would not be resumed in New Zealand.14

The other legal function of gold, as a regulative factor and guarantee of ultimate redemption of the note issues, was no longer practiced, though in law gold was still required to back banks’ notes. This connection had been practically severed in 1914 when bank notes were ‘temporarily’ made legal tender, and by 1930 note issue was entirely regulated by “the volume of credit in conjunction with the commercial habits of the community.”15

The nation had moved light years from the earlier requirement that banks’

note issue was not to exceed the amount of coin [i.e. gold and silver specie], bullion and public securities that it held in New Zealand, nor three times the coin and bullion.16

Thus, Ashwin determined, the only reason for keeping gold in the country was to guarantee redemption of the notes, which was only of moment in the event of the failure of a note issuing bank. This guarantee could be provided for quite as effectively in other ways. The “other ways” would be the provision in the Banking Act, 1908, making notes a first charge on the assets of the issuing bank. This was “all the safeguard needed.”17

Ashwin believed the gold might as well be located in London, where it could earn interest, as in New Zealand, where it was a “dead asset”. And if needed it would serve as an exchange reserve if London balances became exhausted. As sterling was on the gold standard, so long as banks had credit in London, gold could be obtained from the Bank of England.18

He knew this would be controversial…

I am aware, of course, that there is a certain amount of prestige to be gained from keeping a stock of gold in the country, and many people will doubtless regard the suggestion to ship it all overseas as distinctly revolutionary…

but he justified this because…

an analysis of the position shows that we have really no use for it in New Zealand. Further, the stock of gold is an expensive luxury, costing the country about £330,000 yearly.

Ashwin proceeded to further shock his audience and makes what one-hundred years later looks to be an extraordinary statement (emphasis mine).19

Incidentally another £6,600,000 of gold would be an appreciable gain to the banking reserve of the Bank of England, and the resulting reaction on credit in Great Britain could not fail to benefit New Zealand through an improvement in the price of our exports. Thus our own material advantage could be combined with a graceful gesture to the Mother Country.

Having previously claimed that “we have really no use for it in New Zealand” this same gold would “incidentally…be an appreciable gain to the banking reserve of the Bank of England” and “a graceful gesture to the Mother Country.” Did the audience begin throwing rotten eggs at this point?

Ashwin was quick to dispel any fears that the gold would be confiscated (which three years later it was, again)20

I do not suggest that legislation should be passed compelling the banks [to ship the gold to London]. All that need be done is to amend the legislative provisions which require gold to be held in New Zealand, and it may safely be presumed that it would not be long before most, if not all, of it was sent abroad.

Ashwin proposed some legislative provisions to be implemented, specifically.

(a) Fix the sterling exchange standard by making it mandatory for the banks to provide exchange on London...

(b) Bank notes as legal tender to be made a permanent feature of the system. A return to gold circulation being out of the question there is no alternative to doing this.

(c) The note issue to be fully covered by Government securities. This is practically the present requirement under the war regulations…

(d) …Government securities to cover the note issue may be held in New Zealand or London…

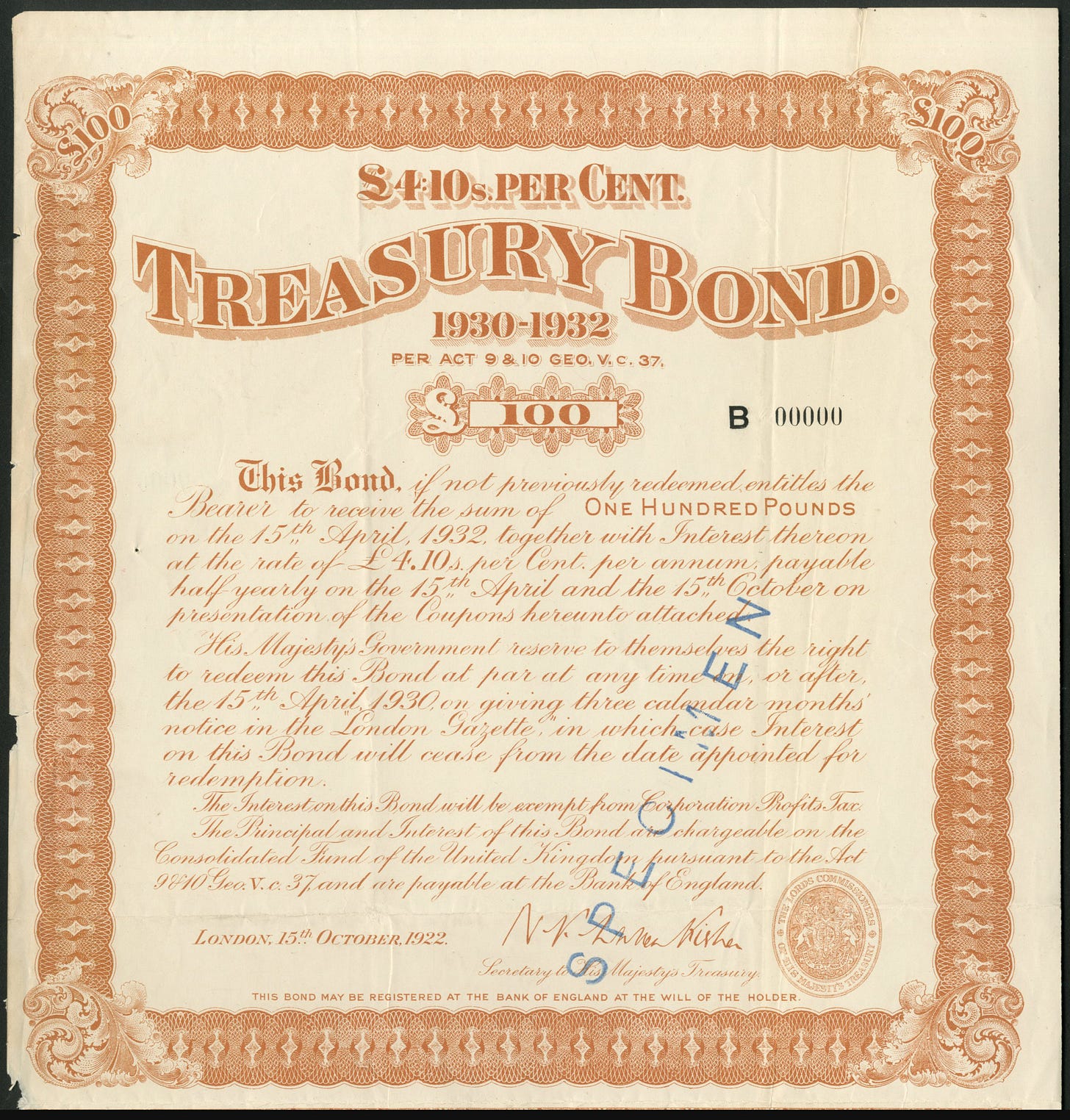

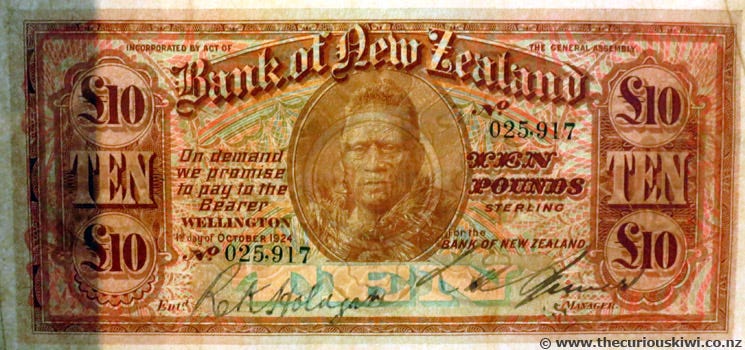

Image footnote.21

The central bank planners were intent on the complete detachment of notes from physical gold, and removing that gold from New Zealand to London.

Uniform Note Issuance

The other reform Ashwin proposed was a uniform note issue. For banks, this was a radical move. At that time six banks produced their own notes, though other banks’ notes were generally accepted by all banks. Because of seignorage, note issuance was a profitable business.

Uniform note issuance could be implemented in the same manner as the Bank of England.

Accordingly, I suggest that while making the other necessary changes in the banking laws the opportunity be taken to set up a non-political note issue board whose functions would be similar to those of the bank issue department of the Bank of England…

Furthermore, note issuance would be secured by government debt.

the board would be bound to keep its funds invested as closely as possible in Government securities…

Ashwin claimed that the “only difference” would be the holder of the debt, changing from the six banks to the single note issuing ‘board’. This was untrue. There was another profound difference.

This step would ensure all notes in circulation were backed by government debt, unlike the mix of specie coin, bullion, and government securities as was the case at the time.

For the first time New Zealand’s currency would not be backed by any physical asset.

This was a profound proposal, certainly the equal of his earlier ‘suggestion’ that New Zealand’s gold should be shipped to London. It would also significantly expand the market for New Zealand Government debt.

A Central Bank for New Zealand

Ashwin concluded his speech by stating that

the establishment of a note issue board, which, by the way, might in due course form the nucleus of a central bank…

The speech itself must have taken at least an hour with Q&A. If there was a Q&A afterwards, notes of this would be almost as revealing as the speech itself. If the reason for Ashwin’s essentially public anonymity was for reasons of Treasury’s plausible deniability if the speech’s reception was too controversial, they need not have feared.

Maybe it was the result of the distraction caused by the depression taking hold. But not only was their no public discussion in the press, there was apparently no public response from Chambers of Commerce and other business associations either. This was remarked on in the Letters page of the Evening Post a few days later, the writer observing that “not even a mild protest seems to have been made.”22

Ashwin made a number of claims to justify ‘his’ position. These need to be examined. And there was a response from both the public and the banks. But first, stage two of Treasury’s central bank charm offensive was to appear later that year.

See full texts of some of the documents used in Part 4.

Next: A Prussian’s Wiles

Previous: Central Bank Conspiracies

Home: New Zealand’s Financial Resets

“Money and Banking in New Zealand”, Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Wellington (1963) pp10-17.

The exchange position, instead of improving, is becoming increasingly difficult. The disparity is too great…the best means of affording relief is through the operations of a central bank with ample powers to effect and control exchange operations…I have been in constant communication with bankers and other financial experts…this week a conference…has been arranged with the object of considering the application of the recommendations of the Imperial Economic Conference to the exchange system of New Zealand…this measure might be further developed and assisted by the creation of central banks…as recommended by the Genoa Conference." … SOUTHLAND TIMES, 11 SEPTEMBER 1924, PAGE 7

For Ashwin’s official biography see The Encyclopedia of New New Zealand.

At some time in 1930 Ashwin was promoted to Assistant Accountant.* Treasury at that time had around one hundred employees.**

* https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4a22/ashwin-bernard-carl

** https://teara.govt.nz/en/zoomify/34932/treasury-staff-1935

“small deception“

Though his ‘true’ identity was revealed in some of the newspaper coverage that followed, Ashwin was variously referred to as being Treasury staff (Evening Post - 6 June p), British Commissioner (Dominion - 6 June, p10), Mr. Ashwin (Dominion - 6 June, p13), a prominent accountant (Auckland Sun - 11 September).

The respected history of money in New Zealand From Beads to Banknotes in a brief discussion on the creation of the Reserve Bank doesn’t mention Ashwin’s Treasury role either.

…in an address in Wellington, B.C. Ashwin suggested…

Hargreaves, R.P., “From Beads to Banknotes”, John McIndoe Limited, Dunedin (1972), p 163.

The Secretary here is equivalent to a Chief Executive.

All major political parties broadly supported the idea of a central bank, though they saw one as having different purposes. There was a political movement that opposed a central bank. Political stances will be addressed in the next part of this essay series.

Given the controversial and consequential nature of what was being proposed, Ashwin’s speech must have been at the very least made with the knowledge of banks. Among other issues, they were going to lose their gold (from New Zealand) and their profitable note producing business.

The speech was published in November of the same year in The Economic Society of Australia’s publication, the Economic Record.

The speech is considered “(a)n early indication of his promise”, and Ashwin was amply rewarded for fronting the opening salvo of the moves to found a central bank in New Zealand. In 1931 he was promoted to second assistant secretary,* and eight years later in 1939 he was promoted to Secretary to the Treasury and became one of New Zealand’s most powerful and influential figures; one of the outstanding civil servants of his generation. Ashwin retired in 1955 and the following year was appointed a KBE. Is there any doubt his 1930 speech was official Treasury policy.

DOMINION, 6 JUNE 1930, PAGE 10

DOMINION, 6 JUNE 1930, PAGE 13

DOMINION, 6 JUNE 1930, PAGE 15

EVENING POST, 6 JUNE 1930, PAGE 10

EVENING POST, 6 JUNE 1930, PAGE 11

A few days later the Christchurch Press provides an example of the brevity of most of the press coverage. PRESS, 9 JUNE 1930, PAGE 10

More coverage here.

WAIKATO TIMES, 10 JUNE 1930, PAGE 10 - “NO USE FOR GOLD.”

POVERTY BAY HERALD, 10 JUNE 1930, PAGE 6

HOKITIKA GUARDIAN, 10 JUNE 1930, PAGE 2

HOKITIKA GUARDIAN, 13 JUNE 1930, PAGE 5

ASHBURTON GUARDIAN, 13 JUNE 1930, PAGE 4

KING COUNTRY CHRONICLE, 14 JUNE 1930, PAGE 3

WAIPA POST, 14 JUNE 1930, PAGE 7

OTAGO WITNESS, 17 JUNE 1930, PAGE 28

WANGANUI CHRONICLE, 26 JUNE 1930, PAGE 13 - “DEAD ASSET; GOLD IN BANKS

Coincidentally(!) Ashwin’s speech had the same title as the Neimeyer Report which would be Tabled in Parliament presented to the Prime Minister eight months later. More on Otto Neimeyer in the next essay of this series.

A high rate was good for exporters, who were the source of the nation’s income. But it was unacceptable to the population because most manufactured goods, including consumer goods, were imported from Britain. A high exchange-rate meant high prices for everyone.

“exchange-rate was set independently“

Rates did vary between banks. Though competition did keep exchange-rates reasonably aligned.

“previous two years“

[ADDENDUM: After publishing I realised I misread this. Ashwin had said earlier that “for the last financial year ended on 31st March, exports practically balanced imports”. By the previous two years, it’s clear Ashwin was referring to financial years 1927/28 and 1928/29.]

Ashwin was misleading his audience. According to a news report a few weeks later* the surplus of the preceding two years had completely disappeared, and exports were at parity with imports for the year ended 31 March 1930. Ashwin, would have known this.

* HOKITIKA GUARDIAN, 20 JUNE 1930, PAGE 2 - BANK OF NEW ZEALAND; ANNUAL MEETING OF PROPRIETORS.

“function of the trade balance“

DOMINION, 6 JUNE 1930, PAGE 13

As the whole system was governed by the rise and fall in the London balances of the banks, with a traditional bias toward keeping rates of exchange stable…B. Ashwin

“all things being equal”

an approximate trade balance between New Zealand and Britain.

”close to the cost of shipping gold”

because New Zealand was on the sterling exchange standard.

That is, both Britain and New Zealand were using British sterling currency; the sterling exchange meant Britain paid New Zealand exporters in sterling, and New Zealand importers paid British manufacturers in sterling. Banks kept these balances in London. If trade was balanced, or as was the case with New Zealand, in surplus, then debt was not required to fund trade. This being the case, because Britain was on the gold standard, some argued that the exchange-rate should be the per cent cost of shipping gold between the two countries; about 1.5% at the time.

The exchange rate depreciated further in the year ‘till the point where £1 sterling cost £NZ1.10 (i.e. 10%).

PRESS, 20 NOVEMBER 1967, PAGE 1

“wonder he spoke“

As it turned out there was no public coverage of Ashwin’s speech in Australia (Australian national archive of newspapers: https://trove.nla.gov.au/) though a financial periodical, Wild Cat Monthly did report on it, which itself was reported in the Christchurch Press (PRESS, 15 JULY 1930, PAGE 12). There may have been diplomatic exchanges between the two countries. Research for another day.

“experiencing significant stress“

As early as October 1929, barely two weeks after ‘Black Thursday’ when Wall Street crashed over 10%, the Christchurch Press reported under the heading “AUSTRALIAN FINANCE; FEELING OF DEPRESSION”

…there are the heavy Commonwealth and State loan commitments to be met in the near future, the stringency in the London money market, the unusually low trading balance in London of Australian banks, the decrease in the price for wool…PRESS, 9 OCTOBER 1929, PAGE 12

New Zealand had in effect gone off the gold standard in 1914 (see here). Ashwin’s statement was true but misleading. New Zealand was on a sterling standard, but sterling was on a gold standard. So New Zealand was on the gold standard by proxy.

“Keynes“

Keynes is supposed to have described gold as a “barbarous relic” in 1924, though it is unlikely he was the first to have expressed this sentiment.

“gold was a “dead asset””

Ashwin is being deceptive. Gold in a bank’s physical possession was not and could never be a “dead asset”. Gold was the asset. Everything else was debt (this what banker J.P. Morgan meant when he said “money is gold, nothing else”). In one’s possession, gold had zero counterparty risk. Therefore, it could not generate an income (i.e. interest). Interest is a feature of risk. But gold as an asset that allowed a bank to generate debt was a different matter. The debt that was created could generate interest because there was risk. But not physical gold. Of course Ashwin knew this. He was creating a narrative.

“£330,000 per annum”

Equal to one-half per cent of the advances outstanding. The amount of gold was misreported in the next morning’s Dominion as £8.6M (based on Ashwin’s claim that 0.5% was £330K).

Overdraft rates, which had just increased by 0.5% in February to 7%*, were “well over pre-war rates.”** of 5.5%.***

* https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ST19300225.2.23

** https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TDN19300308.2.15

*** https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19300916.2.136.9

For the history of the Banking Amendment Act (1914) see:

“a pure luxury“

The June 1925 issue of the Federal Reserve Bulletin reported Chancellor of the Exchequer Winston Churchill describing the return of gold as circulating currency as “an unwarrantable extravagance”. …Federal Reserve Bulletin, Vol. 11 No. 6, June 1925, pp 369. Source.

“gold circulation had practically ceased”

If true and it had ceased even in countries on a gold standard, this is Gresham’s Law in action, where “bad money drives out good.“ The expansion of unbacked notes as debt instruments was a global phenomena. In essence Ashwin was using a phenomena created by bankers, that is the disappearance of circulating gold coin due to more unbacked paper notes circulating, to strengthen his argument for more unbacked (by anything real) paper notes. The audacity is remarkable.

[ADDENDUM: 26 June 224 — The 1927 World Economic Conference in a reference document, the Memorandum on Currency and Central Banks 1913-1924, states (p 6) “By the middle of 1925…there were…thirty countries whose currencies were…based on gold.”]

“practically severed in 1914“

i.e. the law that Ashwin was arguing should be repealed. See:

Sinclair, K. and Mandle, W.F., “Open Account”, Whitcombe & Tombs Limited (1961), p27. Open Account is a history of the Bank of New South Wales in New Zealand from 1861 - 1961.

Ashwin felt it was the only real safeguard, even under the pre-war system, as gold, being legal tender, could then be demanded in withdrawing deposits, and in the case of a run on the bank the stock of gold might conceivably have been absorbed in this way.

This is misleading. The nature of a bank’s assets was changing, moving from the traditional gold with some Government debt securities to increasingly higher proportions of sovereign debt. Regulations under section 44 of the Finance Act, 1916 allowed to eliminate gold from their assets, though they all continued to hold it. So, while the note may have been ‘secured’, it was increasingly likely this security was a sovereign debt instrument, not money.

Britain had left the gold standard in 1914 at the start of the war, and simultaneously withdrawn gold specie sovereigns and half-sovereigns from circulation. It returned to the gold standard in 1925, though gold specie didn’t return to circulation. Notes could be redeemed for gold only at the Bank of England, and only for bars of approximately 400 troy ounces, an option out of reach for most people.

Britain suspended the gold standard just over a year after Ashwin’s speech, in September 1931. Initially the suspension was ‘temporary’, though the gold standard was never reinstated.

“shock his audience“

I’m projecting. We don’t know the audience reaction as it wasn’t reported in the press. But to the knowledgeable modern ‘ear’ his proposals taken together are shocking.

“it was, again“

This time from the banks. The first time was from the public.

Public gold confiscation.

Bank gold confiscation.

This bond document has interest of £4.10s per Cent. Twenty shillings per pound so this is 4.5%.

That does not mean their was no public opposition; there was, which will be examined in the next essay in this series.

“raised comment” EVENING POST, 12 JUNE 1930, PAGE 12 - BANK EXCHANGE (To the Editor.)

Ah, the hell for Humanity that money use creates, eh? I suggest We do all We can to remove that tool in all its forms. We CAN do so.

The Foundational Function of Money (article): https://amaterasusolar.substack.com/p/the-foundational-function-of-money

Why Free Energy Technology Is Suppressed (article): https://amaterasusolar.substack.com/p/why-free-energy-technology-is-suppressed

Heart-Driven Economy vs. Greed-Driven Economy (article): https://amaterasusolar.substack.com/p/heart-driven-economy-vs-greed-driven