NZ Financial Resets: Part 4e: Treasury Beguiles and A Prussian's Wiles: An Orchestrated Litany of Lies - #3 and #4

Dissembling, distractions, deceptions...and does the New Zealand Government threaten the banks?

“One kiss, my bonny sweetheart, I’m after a prize to-night,

But I shall be back with the yellow gold before the morning light”

The Highwayman, Alfred Noyce (1906)

Next: 1933 - The Prize: A Marxist Theory Applied

Previous: New Zealand's Financial Resets: A Central Bank Interlude

Home: New Zealand’s Financial Resets

A Scoundrel’s Refuge

The 1929 New York stock market crash had compounded the effects of the economic slump being experienced in New Zealand. In many ways this helped the London banking cartel; it added another layer of complexity and increased the public’s confusion between cause and effect of what was by 1930 already being called a depression. A confusion that well organised conspirators could take advantage of, and the London bankers did.1

From the opening of their campaign to establish a central bank and disconnect gold from currency and banking, the London bankers dissembled, distracted, and deceived the population. With authoritative messaging they laid the groundwork by lying-by-omission about the root causes of the ‘wobbling money.’2

Treasury and Niemeyer made different contributions to the deception.

First, the Treasury’s Ashwin identified the ‘problem,’ giving an obvious misdiagnosis by calling the effect the cause, while simultaneously shifting focus onto the four Australian banks. A clear case of using that last refuge of scoundrels, patriotism, it was a crude strategy but it worked. There was little initial public reaction but after Niemeyer’s visit and Ashwin’s speech was published in the Economic Record things started to move into the public domain.3

A Classic Bait, Switch, Distract

The London bankers were fishing, the Australian banks were bait and the exchange-rate was the switch.

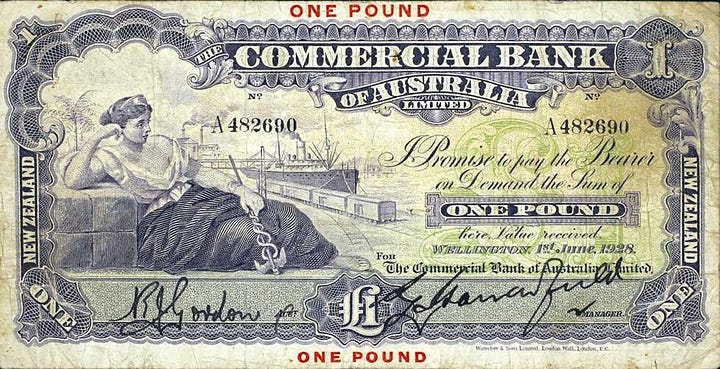

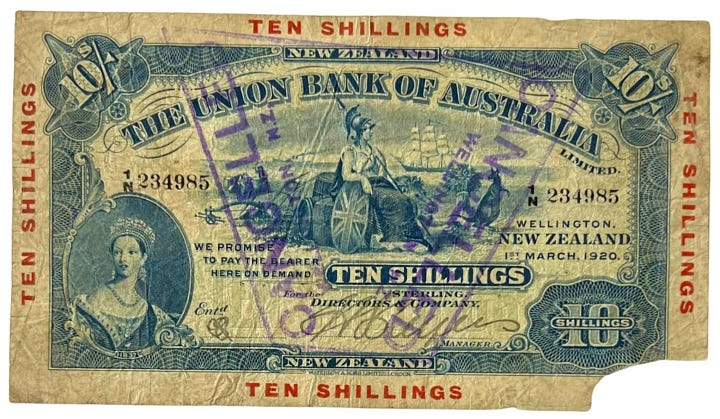

The Bait: Four Australia Banks

Ashwin’s claim was the four Australian banks were exploiting New Zealand and were responsible for the high exchange rate; an important issue affecting everyone. He never supplied the evidence to support his claim. Because there was none. But facts didn’t matter, Ashwin was fishing. It wasn’t long before the Treasury’s prey nibbled and in late February 1931 an important politician was hooked.4

Prime Minister George Forbes wrote to the banks asking them to explain. The Treasury’s view was not news to the banks; they were “well aware of the line of thought, in the Treasury, which led to Forbes’s [sic] enquiry”.5

The Switch and Distract: The Sterling Exchange-Rate.

As a distraction and misdirection the Australian banks/exchange-rate issue was the perfect choice. Everyone had a view on both, and the country was divided every which way. Australia, as a neighbour and close competitor, was an ideal whipping boy and Australian banks probably perfect. Banks were easy to hate.6

my ships have all miscarried. My creditors grow cruel. My estate is very low…7

And best of all from a distraction perspective, any intervention from politicians would be futile for improving the actual condition of the population. Politically, it was a zero sum game. But in the political environment of the day the accusation sufficed and all eyes turned to the four Australian banks. Not surprisingly the banks didn’t take this accusation lying down and “they fought a long and somewhat inconclusive defensive action.”8

This was…

LIE #3

The Australian banks were not responsible for the exchange-rate. The exchange-rate was dynamic and the consequence of many complex interacting factors.

The Treasury, as bankers, would have known this obvious fact. Which is how we know the misdirection was intentional. Moving the focus onto the Australian banks and the exchange-rate consumed many futile hours of speaking time in parliament and thousands of words in the press for the next few years. In that alone it was successful. But it also allowed the London bankers and the Treasury to provide the solution.9

The solution was for New Zealand to take charge of its own financial matters, in itself a reasonable idea. There had been talk in the past of nationalizing the Bank of New Zealand but, after a brief revisit, this idea was dismissed.

Anyway, what the public and politicians wanted didn’t matter. The London bankers, as represented by Niemeyer’s internationalist vision, were pushing for a central bank10

that realised their ambitions.

They needed a new institution with new people and no institutional memory. A blank slate.

It was among the dust and debris of the Australian banks—exchange-rate debate that the idea of a new ‘independent‘ New Zealand central bank began to be solidified in the minds of the public.

There was one more obstacle. Gold was still the key.

The Golden Key

Permanently disconnect gold from banknotes

The Government, using the banks, had confiscated the circulating gold-sovereign from the population at the start of war in 1914 when banknotes were made legal tender. In order to disguise this confiscation it had been done on a ‘temporary’ basis and the process dragged out over a number of years while the consciousness of the population was changed. By the early1930s, with the enabling legislation due to expire, the banks and the Treasury were acutely aware of the risk of notes being returned to ‘payable on demand.’11

To justify permanent confiscation of gold Ashwin had to dissemble. He claimed that prior to the war “we had a gold circulation but the sovereign played no greater part in the actual system than the silver and bronze coins.“12

This was the opposite of the truth and was…

LIE #4

Before August 1914 the gold sovereign was the whole basis of the “actual system”13

By saying the sovereign was no more significant than other circulating coin, Ashwin was disconnecting the actual value of the currency—the physical gold specie coin, the sovereign—from the name and symbol used to represent the value. Ashwin was saying the value’s name, the pound (symbol £), was the basis of the system, not the physical item. This was a bookkeeper’s mind speaking and he was using a banker’s trick of language.14

The word for this is fraud.

The ‘note-issue’ issue was entwinned with the gold issue because though ‘emergency’ laws and proclamations had suspended banks requirement to back their notes with gold, the laws were temporary and due to expire. A £1 banknote was still in theory a receipt for a gold sovereign coin or silver equivalent. And New Zealand banks retained a large amount of gold on their balance sheets as a general asset, used to support all their business.

This was a problem. But it could also be used as a threat to bring the banks into line. The London bankers wanted the gold out of New Zealand, under the watchful eye of the Bank of England, at the lowest price possible.

ASIDE: Another Distraction—The Douglas Credit Movement

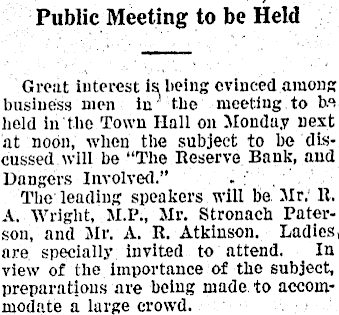

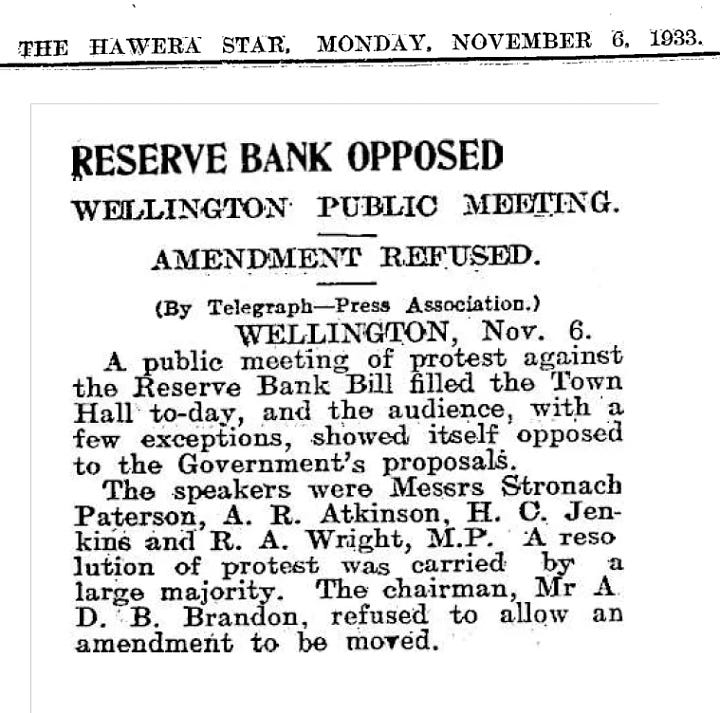

The most politically assertive and organised movement opposing the visions of a central bank presented by the various parliamentary political parties was the Douglas Credit movement, which ultimately manifested in New Zealand as Social Credit. It was “the biggest movement in the world” according to one 1933 press report, and looking through the newspapers of the day it filled many community halls and volumes of columns in the press and Hansard. And it was another distraction, what today we might call a psychological operation.15

This is a bold claim, and needs justification, but first one more piece of the puzzle needs to be established, so Douglas Credit will be addressed in the next essay. For now it’s sufficient to recognise that there was a massive opposition by the population to a central bank, whose energies were sapped by the Douglas Credit movement. Douglas Credit successfully controlled the opposition and corralled the debate within an Overton window of contained parameters. There are over six thousand press items and nearly two thousand advertisements between mid-1925 (the first mention) and 1940 alone.16

But opposition to the proposed Reserve Bank was not just from Douglas Credit. For example Stronach Paterson, a speaker at the above meeting, was a prominent businessman of the day with no apparent ties to the Douglas Credit movement.

* See footnotes for links.17

A Negotiation? Or…

While the distractions of the exchange-rate, the Australian banks, and the Douglas Credit movement percolated in the foreground for several years, in the background the real business was being transacted. As the central bank legislation progressed through parliament, a dispute developed between the banks and the government over the gold held in the banks vaults. Once it was ‘agreed’ the new Reserve Bank would take possession and ownership of the gold, the dispute evolved into an argument over the sterling-currency price the government would pay for the gold.18

Because of the sterling ‘printing’ and consequent currency debasement over the previous two decades the sterling price of the gold in the £1 face-value sovereign was about 1.5 times that. The banks wanted the market value, ~£1 10/- per sovereign (i.e. £1.5). The government were determined to pay the nominal value of £1 per sovereign.19

In 1933 the chairman of the Associated Banks, Mr. J. Grose, made a statement to the press.20

”This gold was purchased with the banks’ own assets, and was, and is, as undeniably their own property as are their premises. To take this gold at anything less than its real value would be straight-out confiscation.”

The claim that the gold “was purchased with the banks’ own assets“ is, to be generous to Mr. Grose, a stretch. Some of the gold he was referring to was the gold that had actually been confiscated from the population nineteen years earlier, an event Grose is silent on. He was referring to a confiscation of sterling-currency; this was his “real value.”21

…A Shakedown?

Ultimately the issue was resolved and the Government won the gold at its desired lower price, though it’s unlikely they won the argument. Worse, the government may have used coercion to achieve its aims. Almost in passing the author of the respected history of New Zealand banknotes Beads to Banknotes, R.P. Hargraves, states

their protests were to no avail for the government hinted that the law making notes legal tender and hence inconvertible could easily be left to lapse in 1935 whereupon all banks would be faced with the need to hold large stocks of gold coins in order to pay out gold on demand to any of their noteholders.22

Unfortunately Hargraves doesn’t give a reference. But the fact it is Hargraves lends this claim serious gravitas. If true it’s a revealing statement that indicates desperation by Treasury. Far worse than just blackmail, the Government were threatening to possibly collapse the entire financial system.23

Is this true? Until proven with documents we can’t say. Either way it’s an interesting idea. If banknotes and deposits etc. had been allowed to become redeemable for gold it would have been very disruptive to banks business operations. It would have required a major balance-sheet reorientation—a multi-year process. At worst it could have resulted in the collapse of some of the Australian banks New Zealand operations. There would have been no positive outcome for customers. No matter, it never happened.24

Why would the Treasury be desperate?

Simple. Remember, the Treasury were New Zealand agents for the London bankers. With essentially one product. Sterling-currency debt. Which they had disconnected from any intrinsic value in 1914 when they had stopped redemption of banknotes. And they printed sterling…and printed…and printed...and caused the depression.25

And now sterling-currency, the only product the London bankers had, which had completely contaminated all nations using it, was valueless. They had printed so much sterling-currency since 1914 there wasn’t enough gold to reset the currency back to gold at the price needed to give their sterling product any real value.

These bankers have more wealth and power than most people can even begin to imagine. If they couldn’t fix sterling to something of value they stood to lose, maybe not everything, but certainly a lot. They needed a central bank, in a certain form, which would allow them to connect sterling to something of value.

That’s why the London bankers and their agents, the Treasury, may have been so desperate. If what Hargraves says is true.

Why did the banks go along with the “confiscation“ of ‘their’ gold?

The four Australian banks in particular had been under attack for several years. On top of the many challenges doing business during a depression, they were fighting the exchange-rate accusation, the London-reserves issue, and had initially resisted the gold-ownership issue. The first two were distractions. The last one wasn’t. The banks lost the ownership fight. Next came the gold/sterling-price issue. They lost on the sterling-price. Possibly under threat. Why didn’t they just pack up and head home?

Probably because it was just business. And bankers can do math. Despite the significant erosions on their property rights, they were expecting to be rewarded with a sizable piece of the prize.

And oh…what an incredible prize.

Crime is so much easier…and so much safer…

Using a book than physical banditry.

See full texts of some of the documents used in Part 4.

Next: 1933 - The Prize: A Marxist Theory Applied

Previous: New Zealand's Financial Resets: A Central Bank Interlude

Home: New Zealand’s Financial Resets

“further layer of complexity“

The U.S. was a significant creditor as well as trading partner of Britain, so of course this event compounded New Zealand’s problems. Britain was New Zealand’s main destination for exports and London’s financial district was where nearly all New Zealand’s international transactions were cleared and settled.

“already being called the depression“

Or the slump. The terms depression or slump were being used interchangeably to describe what was happening to export prices. See Papers Past for examples.

New Zealand historian Tony Simpson described the depression era statistics as “a chamber of horrors”…Simpson, T., The Sugarbag Years, An Oral History of the 1930s Depression in New Zealand, Alister Taylor Publishing, Martinborough (1974) p 8.

“obviously misdiagnosing“

Therefore intentionally.

“last refuge of scoundrels, patriotism“

Quote, paraphrased here, attributed to British political observer and essayist Samuel Johnson.

“things started to move into the public domain“

This is not to imply the press were not already reporting on the Australian banks, or the exchange-rate, or both in conjunction with each other. They were.* But the campaign was stepped up to a new level with Forbes’ enquiry.

* A search of Papers Past for “Australian bank” for example returns several hundred results, not all about the exchange-rate, for 1931 alone.

“Ashwin’s claim…exploiting New Zealand“

The exchange-rate was a complex function of trade with Britain. The fact that trade, hence the exchange-rate, was in such disruption was an effect, or consequence, of the issues discussed previously. For Ashwin’s claim see New Zealand’s Financial Resets: Part 4b: 1930 - Treasury Beguiles

“well aware of the line of thought“

[ ] added.

Sinclair, K. and Mandle, W.F., Open Account - A History of the Bank of New South Wales in New Zealand 1861-1961, Whitcombe & Tombs Limited (1961), p 192.

This could have been as a result of Ashwin’s June speech but I wouldn’t be surprised if there had also been private communications between the Treasury and the banks.

“Banks were easy to hate.“

It was an effective campaign; there are plenty of examples* in the press of the banks being blamed for a variety of ills. This example, a reported quote in the Parliament dryly summarizes the situation for banks. While proposing arbitration in the event of a dispute over the price of gold in banks vaults Mr. Wright** “knew the banks were unpopular.”

GISBORNE TIMES, 3 NOVEMBER 1933, PAGE 5—RESERVE BANK

Or as the author of the history of the Australia and New Zealand Bank put it “‘the banks’ as representatives of the evil powers of high finance”…Butlin, S.J., Australia and New Zealand Bank - The Bank of Australasia and the Union Bank of Australia Limited 1828-1951, Longmans (1961) p 390.

* “plenty of examples“

Just a search of Papers Past reveals how contentious an issue ‘the banks’ was, especially the Australian owned ones. There are 221 returns for a 1933 search of “Australian banks”. Not all are directly relevant to the exchange-rate issue, but it is indicative of the close coverage in the press they received.

** “Mr. Wright”

The article doesn’t give detail. Looking at the House of Representatives Roll this man is the only option. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Wright.

Merchant of Venice, Act 3 Scene 2, William Shakespeare

“intervention from politicians would be futile“

Any ‘successful’ intervention would satisfy half of the country, offend the other half. Doing nothing they would be accused of doing nothing…by everyone. Politicians couldn’t change the rate by fiat, and even if they achieved a new rate, whatever mechanism they chose there would be a market response. So the ground would begin to move even as they found their feet (is this mixing metaphors? apologies if so).

“Not unexpectedly the banks“

The banks were able to show the Treasury’s claim had no basis, was a gross simplification of their business, and overall had no foundation. For example, at the Bank of New South Wales

no one seems to have shown that New Zealand funds has in fact, in any quantity, been used in this way. Davidson was able to deny that his bank was following this practice…Sinclair and Mandle (1961) p 192.

The 'Wales General Manager, Sir Alfred Davidson, was unimpressed with the Treasury’s line of argument. He wrote to his Chief Inspector that “funds held in London by the Bank are not earmarked for the specific needs of Australia or New Zealand…It is a fundamental feature of banking that the bank’s reserve…is available for whatever calls its customers make.”

The Bank of New South Wales went further. In what its biographers describe as “the only occasion when the Bank took an open and leading part in a political action in New Zealand,“ the Wales “initiated one of the most strenuous political campaigns in New Zealand’s history.“

Davidson arranged for a highly respected New Zealand born academic monetary policy economist, Professor D.B. Copland from the University of Melbourne, to present the contrary argument, which he did in a series of articles in the Evening Post* in April 1931. And more. He debunked the Treasury thesis and worse from their perspective Copland argued the benefits of a high exchange rate—which as an exporting nation were obvious—and believed there was room for it to go higher. Another big subject. Another distraction.

* “Evening Post“

Part 1 EVENING POST, 20 APRIL 1931, PAGE 8 - ADVERSE EXCHANGE, DOMINION POSITION, EFFECT OF PRICE FALL

Part 2 EVENING POST, 21 APRIL 1931, PAGE 10 - EXCHANGE FUNDS, WHY THE RATE VARIES, INFLUENCE OF EXPORTS

Part 3 EVENING POST, 22 APRIL 1931, PAGE 9 - ADVERSE EXCHANGE, AUSTRALIAN FUNDS, EFFECT ON NEW ZEALAND

Part 4 EVENING POST, 23 APRIL 1931, PAGE 12 - FREE EXCHANGE, A. USEFUL CORRECTIVE, HELPFUL TO EXPORTERS

“consumed many futile hours“

And probably on the radio, in the pubs, markets, drawing rooms…

The idea of a central bank was not new and had been discussed widely in the press for many years. Bank of England news was regularly reported on. The establishment of the U.S. Federal Reserve system (1913) was covered, as were the various debates over the establishment of central banks in New Zealand, Australia, and many other countries over the years. See Papers Past for over 10,000 results for “central bank” alone (though many are not relevant to this work) going back to 1859.

“The London bankers…Niemeyer’s internationalist* vision, were pushing for a central bank“

But not just any central bank, and more than a bank of currency issue. They had a vision for the type of central bank they wanted. Details in the next essay.

* Today we call this ‘globalism.’

“consciousness of the population was changed“

By war and depression, and legislatively by rolling over or amending legislation (e.g. the Finance and Banking Amendment Acts) and using Proclamations. And time.

“legislation due to expire, the banks“

Who had created large amounts of sterling currency, theoretically receipts for physical gold or silver coin.

“payable on demand“

Meaning banknotes would no longer be legal tender, and would once again be redeemable in gold specie coin on demand. The many implications of this would be complex and significant. One implication was bad enough. Because of the sterling ‘printing’ and consequent currency debasement, the sterling value of the gold in the £1 face-value sovereign was about £1 10/- (i.e. £1.5).

Even though banks in theory had enough gold value to back their notes, there were at least two potential problems:

gold was a general balance sheet asset, and

not all the gold was specie coin, some was bullion. So they would need to buy some in; this wasn’t easy. Sovereigns were no longer being minted in circulation quantities.

“the gold sovereign was the whole basis“*

Including the note issue which gold had regulated. This was no longer the case due entirely to the debasement caused by the ‘printing presses’ and the legislation that facilitated this. A fact Ashwin and Niemeyer were silent on. Instead, because now “notes are quite subsidiary to credit” there was no regulative need for gold, unless the bank failed, and if it did “making notes a first charge on the assets of the issuing bank provides all the safeguard needed.” In other words, if a bank failed, a bank’s Notes would be redeemed in…debt.

This is about language.

Banking is essentially just accounting. Lists of numbers in ledgers. These accountants, the bankers, wanted to separate the value—the gold and all the energy and effort that goes in to its production—from the symbol. A symbol they could create from nothing in a ledger. It is much easier to write the symbol in a ledger than work to mine the gold and mint it into the sovereign coin. Crucially they wanted

the symbol to be the value.

Silver coin divided** the value of the gold sovereign, and bronze divided the silver. Financial instruments and ledger banking, the core of the commercial financial system, hinged and were based on the fact gold specie coin circulated. The reason why gold coin was not in everyday use was it didn’t need to be. It was too valuable.

Silver was sufficient for most transactions as a physical medium of exchange. Gold’s primary purpose was as a store of value. When sovereign values were needed (i.e. multiples of £s), banknotes were only acceptable as a medium of exchange because they were receipts, payable on demand, for sovereigns. Banknotes were preferred as an attempt to reduce risk for both parties to a physical transaction.*** See here for more.

* All quotes Ashwin — EVENING POST, 6 JUNE 1930, PAGE 10

** “Silver coin divided“

Before silver coin debasement in 1920

One sovereign : 22 carat gold : value £1 sterling

One shilling : 92.5% silver : value £1/20 sterling

One penny : bronze or copper : 1/12 shilling = £1/240 sterling.

There were other circulating silver and bronze coins, all a multiple or fraction of the above. See https://en.numista.com/

*** “physical transaction“

As compared to a ledger-entry transaction which doesn’t involve the physical transfer of value.

“a bookkeeper’s mind“

Double-entry bookkeeping and balance sheets.

“and organised“

Organisation takes resources, so the Douglas movement was obviously well funded. This would be an interesting trail to follow. I wouldn’t be surprised if banking was at the end of it.

“one 1933 press report“

MANAWATU TIMES, 23 AUGUST 1933, PAGE 8—Douglas Social Credit

“the Hansard“

New Zealand’s parliamentary record of debates

https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/

“Douglas Credit will be addressed”

I’ve no intention of delving into the Douglas Credit economic theory or the debate that was held in New Zealand. As I said, it was a distraction. But there was one important element of Douglas Credit policy which needs to be addressed. Because the Douglas Credit operation is being repeated today. It’s just got a different name. Now it’s called Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

“there are over six thousand“

From Papers Past. This is just the search term “Douglas Social Credit“ alone. “Social credit” gives many more.

“two thousand advertisements“

For meetings, booklets, study groups…

DOMINION, 3 NOVEMBER 1933, PAGE 12—RESERVE BANK BILL, Public Meeting to be Held

HAWERA STAR, 6 NOVEMBER 1933, PAGE 7—RESERVE BANK OPPOSED, WELLINGTON PUBLIC MEETING

“central bank legislation progressed through parliament“

The Reserve Bank Bill was finally* introduced on 7 December 1932 while Parliament sat under urgency in what one newspaper described as an “END OF SESSION RUSH.” I’m being only slightly facetious when I say ‘I bet it was becoming urgent,’ because the government had been told at the end of 1931 it “should not expect to be able to borrow in London during 1932.“**

* The process of getting the Bill introduced into Parliament seems torturous. See Papers Past for the blow-by-blow press coverage of this process.

** From Reserve Bank of New Zealand: Bulletin, Vol. 75, No. 1, March 2012 pp38-45.

“sterling ‘printing’“—discussed earlier.

CORRECTION: Post publication I realised the word “ounce” which will be in the email should have been “sovereign”. That’s why editors are necessary!

KING COUNTRY CHRONICLE, 19 OCTOBER 1933, PAGE 5——GOLD IN THE BANKS, WHO OWNS IT? AN OFFICIAL STATEMENT.

“Some of the gold Grose“

By 1933, of the total gold in bank vaults* some would have been the actual gold taken from the population. Some was possibly imported since 1914,** and some was mined in New Zealand since 1914. This last was probably the greatest source of new gold. While industrial mining was always present, smaller scale gold mining took off during the 1930s depression as people who lost their jobs moved from the city to the gold fields in search of income.

A good description of this little known phenomenon is found in Fred Miller’s memoir of his five years panning on the Clutha river Gold in the River.*** Miller had been a senior reporter with the Christchurch Press before he lost his job in 1930. He and his wife moved to central Otago and set up house, initially in a cave alongside the Clutha. They made a living, though not a fortune.

“Gold selling day in Alexandra was always an event. Saturday was the day, and the miners flocked into Alexandra from miles away and the banks were kept busy weighing out pennyweights where in the early days they weighed always in ounces.”…Miller (1974) p 129.

A pennyweight is 1/20th of a troy ounce in the Troy weight system used for precious metals.

“The plain fact of the matter is all the easily won gold in Central Otago has gone.”…ibid p 131.

See the OTAGO DAILY TIMES, 1 NOVEMBER 1933, PAGE 4 for an idea of the gold yields from the region in earlier days.

“paper sterling currency“

Now off the gold standard.

* Gold was always on the asset side of a bank’s balance sheet, the balancing liabilities were always notes and bills in circulation, deposits, and debt owed to other banks. In one way or another they were all theoretically exchangeable for gold, though its physical transfer wasn’t necessarily involved in a transaction. Physical gold wasn’t used in most transactions (it was too valuable), which is what Ashwin (Treasury) was referring to when he lied and said gold had “no real economic significance, as a pound note does the work just as efficiently as a sovereign“…(DOMINION, 6 JUNE 1930, PAGE 15).

Notes were payable on demand in gold, in theory bills also, after a time-delay and a few steps. Deposits could be withdrawn in specie if desired by the depositor. Inter-bank debt was probably rarely settled in physical gold, and only when there was a large credit imbalance.

** Gold half-sovereigns were still being shipped to New Zealand until 1916 when Australia, where they were manufactured, prohibited gold exports. I’ve not done any research into gold flows into and out of New Zealand over the years 1914-1933, but any imports would have been small because of the global prohibition of gold exports.

*** First published in 1946 as There was Gold in the River it was republished as Gold in the River in 1969. This second edition, which aside from the abbreviated title came with an epilogue, was reprinted in 1974 and is the edition used here.

Miller, F.W.G., Gold in the River, 2nd Ed., A.H. & A.W. Reed, Auckland (1974).

“Hargraves, states“

While discussing the banks resistance to giving up ‘their’ gold to the Government during the Reserve Bank debates. If true, I doubt this scheme was dreamed up by politicians. Only bankers/the Treasury would have known how vulnerable the banks were to this.

Hargreaves, R.P., “From Beads to Banknotes”, John McIndoe Limited, Dunedin (1972), p 165.

“if true“

I have not come across this idea anywhere else. But nor do I claim to have read all the relevant documents. I’ve looked in the official bank biographies and read plenty of official documents, and no mention of a government threat along these lines. I’ve not researched any further, though the Treasury and Ministerial files over this period would be interesting. One day maybe.

A detailed analysis of this is beyond the scope of this essay. The key points are:

the banks had grown their note issue from £2M in 1914 to £6M by 1932. But they had also grown their total liabilities from £29M to £61M. The banks likely didn’t possess the sovereigns needed to redeem all their Notes in circulation, and even if they did, the sovereigns were a general balance-sheet asset supporting other business. Notes at that stage were backed by government securities, bullion and coin, and bank-customer advances invested in either war bonds* or discharged soldier’s settlement loans. Or against wool held in store!! In theory if the legislation was left to expire these Notes and some other liabilities (e.g. customer deposits) could be redeemed in sovereigns.

Because gold specie coin was no longer in circulation all the mints that produced sovereigns and half-sovereigns (in Britain, Australia, Canada and India) had severely reduced production. It is doubtful the banks could even obtain the required sovereigns if they needed too. See numista.com for annual production numbers.

The price of gold was 1.5X higher than the gold value in a £1 sovereign so forget about seigniorage. A £1 sovereign would cost £1 10/- plus minting/shipping etc. costs.

The point is the banks would have needed to manage the risk of gold withdrawal and a classic ‘bank run.’ In a short sentence, there is no way Note redemption in specie was ever going to happen.

1914 bank liabilities from New Zealand 1915 Yearbook.

1932 bank liabilities from New Zealand 1934 Yearbook.

“sovereigns“

Or depending on the situation, silver coin or bullion.

* “war bonds“

Bernard Ashwin DOMINION, 6 JUNE 1930, PAGE 15

“Remember“

“redemption of banknotes“

For specie gold coin.

Wow!

Me: 'Vaccines' ... are evil poison designed to kill you!'

Not Me: 'That's terrible! Who would do that?'

Me: 'Bankers!'

Not Me: 'OMG! I Hate Bankers!'

Me: 'Yeah ... Bankers are really evil ... we need to tear down their whole evil financial system'

Not Me: 'I'm in! Where do we start?'

Me: 'Vaccines!'

regards

pb

Good lord man! How incredibly erudite and well researched. Do you write for a living? I'm going to have to go to square one on this. There's just too much I don't know or understand. My father's parents lost all their savings in the 1929 crash - apparently their "lesson learned" (which was repeated ad nauseam around our household which was obsessed with money and 'security',) was "don't put all your eggs into one basket." Poor naive people - not that that's not a good practice, but was that REALLY all they learned? I tend to shut down easily around this kind of stuff - I'll do a bit each day. This is fascinating and I'd love to have you for dinner with a bunch of guests to hear you speak on these matters. Hope you're having a good day Craig. 🤗